Writing about a grandfather I have never seen, should be unusual. Further, writing about him before I write about any other relative including my parents and siblings, should be stranger. And yet, here I am.

What prompted the thought process that helped me start writing about my grandfather is more introspective. I guess I have always been engaged in introspection. Some even considered me to be a dreamer. I used to day dream as a child. But those dreams were perhaps different than others. I used to get lost in thoughts relating to the past, the present and the future, and almost never in fantasy, religions, magic, or whatever else kids normally day dream about.

Those introspection did not always produce believable or satisfactory answers. Therefore I would often take my questions to my elders. The elders that had the misfortune of being the recipient of my incessant questions, used to joke about it. They even named me “Keno babu”, or “Mr. Why”, because of my constant barrage of a standard question – Why things happen the way they do. If someone made a simple comment such as “Look, the moon is emerging over the horizon”, this would have resulted in a question from me, asking why the moon emerges that way. If someone tried to wriggle out of the question with simplistic statements such as “because the moon always rises about once a day”, this in turn would normally result in a further question from me asking why the moon does that daily. Telling me that the reason was that the moon was actually circling the earth, and that the earth was spinning around itself, would have generated further follow up questions – why, why, why. So, the elders had genuine reason to be rather wary of me, the “keno babu”.

But was that a reason for me to now write about Kalimohan Ghosh, the late father of my late mother?

Not directly. I am not sure if Kalimohan Ghosh was an introspective person. From what I gathered, he was a hard working man often away from home, and was engaged with rural people that his children did not really associate themselves with too much in their young lives. Nobody among his family understood him much. A lot of folks benefited from his generosity. He supported not just his own children, seven of which reached adulthood – six sons and a daughter. A number of other relatives including youngsters grew up in his house and got education in Santiniketan, because they were less fortunate than him. Those days, his salary as set by Rabidnranath Tagore, was five rupees per month. I do not know the exchange rate between Indian and American money back in the first half of last century. In today’s money, it would amount to about ten cents.

The foundation of the house was unlike foundations made these days. Earth was removed many feet deep. Then special tight pack clay was brought by bullock carts, along with water. Santhal men and women laborers were engaged in packing that earth manually, beating them with heavy steel weights. For almost a month, the Santhal women would come early in the morning, and work through the day, singing in tune with the beating of the steel weights, packing the earth into a semi-stone consistency. That it took almost a month to pack the foundation slab, was information I got from my grandmother, who outlived her husband for many decades and who was fond of speaking with me about the early days of Santiniketan. It is from her that I learned so many facts, such as that one of my uncles, Montu mama, once got a score of 12 out of a hundred in mathematics in school. He was a naughty boy and did not like to study, and the score was low enough to generate some follow up exchanges involving a note going to his father, my grandfather. The issue was different enough to get embedded in my grand mother’s memory.

My grandmother vividly remembered the unending stream of people that often ended up at their house to meet with “Kali babu”. Kali babu was the short name given by the villagers, to Kalimohan Ghosh. He was to be the recipient of all their complaints, difficulties, expectations, sorrows and joys. This included the Hindu, the Muslim and the tribal villagers surrounding Santiniketan. Just like the foundation for his new house in Santiniketan, Ghosh was the worker laying the foundation of a future society, following the master concept of Tagore, fine tuned and systematized in some of its facets into an evolving master plan by Leonard Elmhirst.

Anyhow, going back to the house – once the foundation for the house was firm – the rest of the construction would be erected over it. Houses did not have pillars. The strength came from the walls. And since brick houses were more costly and bricks were not so common, and since they did not support the local industry, the house was build by mud packed walls re-inforced with bamboo framing. The walls are almost a yard wide. Each material was treated with local knowledge and according to local practice, to prevent rot. The roof was supported with an unusual kind of wood – Palm tree trunk sliced lengthwise into four pieces.

That house, a hundred year old, still stands, and does not suffer from insects eating into the walls. It is a model of sustainability of a kind that has very few parallels within the University compound. However, sustainability, supporting the local industry, low ecological footprint, and living simple – are not mantras for Santiniketan these days. It prefers to imitate others. Not having a socio-economic or cultural compass anymore, and neither any roadmap or a clear destination, it cannot set its own course.

What a tragedy!

Kalimohan’s family had 12 cows, which were kept within the property. His wife maintained them, though she had some helping hands. Milk came from the cows. Extra milk was converted into durable milk products and stored for future use. They had a small paddy field behind their home, which was cultivated for rice. That provided about half the annual consumption of rice. Rice was also used initially for converting to puffed rice, as well as roasting and mixing with jaggery, to prepare rice candies what could also be stored, but preferably in air tight containers, to keep the insects at bay, and that too for a short while.

Life was very different, as little as eighty years ago in Santiniketan. There may have been fifteen to twenty people living in that house which essentially had just two main rooms in the center of the house, and four smaller rooms, barely big enough to fit a bed, at four corners. It had four small varandas facing all four sides.

The roof was originally thatched, but later converted to corrugated iron sheets that were coated with bituminous tar, poured hot and brushed across the surface, both sealing it and disinfecting it. One of the side effects of it was that it would absorb heat from the sun and turn the house into an oven in the warmer months. Erection of an internal false ceiling improved the thermal balance to an extent. But no matter what you did, it would never be as good as the original thatched roof when it came to climate control.

People kept their windows and doors open to let the breeze through, and often slept in the Varandah in the summer months.

Mango trees were planted within the compound to provide shade and also fruits. The mangos turned out to be not too many or sweet, but good enough for extracting mango pulp and with addition of sugar, drying them out as patties that were known as “amsatta”. I remember seeing my grandmother do that before she got too old, and the trees stopped producing too many mango’s, likely from lack of care.

Decay, was creeping into that house even when the children were alive and doing well. NO major trees were planted on the property after the demise of Kalimohan. I remember at least four great trees of different kinds that had been planted by Kalimohan, and that eventually toppled in storms in my childhood years, never to be replaced.

But all this does not explain what prompts me to think about my Grandfather. Folks have been telling me to write about my grandfather. But the reason given to me is different from my own. My grandfather’s work towards rural reconstruction effort of Rabindranath Tagore was important, and has remained more of less out of the mainstream research or documentation of the academia. But, this effort, conceptualized by Tagore, was a key item in Tagore’s view on life, at the local and global level. The Bengal academia has been more or less remained blinded by the more exotic and glittering side of Tagore – his literary achievements. Therefore, there were some that feel, perhaps justifiably, that I should be writing about my grandfather.

I know my grandfather was not averse to writing, although it was a lot more complicated those days to write anything and to ensure that those writings would survive. He was, for the lifestyle he followed out in the villages around Santiniketan, a remarkably productive writer, both in his essays, his journals and his continuous exchanges with so many people. He was well connected not just with the villagers, most of whom did not and could not write, but also with a large number of people among the educated class in India and abroad. His association with Elmhirst alone spanned much longer than the actual tenure of Elmhirst in Sritiketan, and only ended with the death of my grandfather, in 1940. For a man that was a generation younger than Tagore, he passed away a year earlier. I know Ka;imohan lived mostly alone, and died alone. Very few people were home when it had a massive stroke. I remember my uncles discussing that incidence many years later. From that I gathered that, other than Samir Ghosh, the third son, nobody else was home when he had the stroke, and there was nothing anybody knew what to do. Kalimohan passed away quickly and did not linger on paralyzed or incapacitated.

I did not feel the need, and still do not, about writing a book about his work towards fulfilling a social task that Tagore figured Indians aught to undertake. I was no scholar. I did not see anybody really interested to know about Tagore’s efforts with improving the socio-cultural fabric of India. Folks wrote about him only when the author is paid for his/her labor, or when invited to present a lecture somewhere, or see an article about it published somewhere. The effort must benefit the writer in his/her personal career, more than it would further the effort initiated by Tagore, to serve as an example of a duty for future generations. We are the future generation, and we do not believe in any duty other than lining our own pockets. So, who does one write a book for? To me, a book is not just what it is about, but also who it is for.

There has been a serious deterioration of the moral fabric of the middle class – I often felt. Or perhaps the middle class never really had a moral fabric, and that I only stumbled upon it lately.

Either way, I was not too keen to be “Me-too” in the long chain of folks that write non-fiction books on things that only a handful of academics were interested in, and the subject was to remain within the academia and the libraries.

Tagore mistrusted the bead counting, chanting masses and their disinfected temples, libraries and castles, and the professional pundits. These so called pundits possessed knowledge that were mere barren copies of old chants and past practices and theories. There was often no effort at creating new knowledge, nor ideas being tested and tempered by real endeavors in life. Tagore questioned the belief that spiritual enlightenment could come from sanctified pages of books alone. For him, salvation came from identifying with the sweat of toil of the common man, and with nature. Some of that had rubbed off on me too, although I have never seen Tagore either. Both my Grandfather, and Tagore, passed away a decade before I was born. I knew a lot of it rubbed off on my grandfather.

Kalimohan’s interaction with the Brahmo Samaj religious movement was a case in point that helps me identify a similarity in our cognitive behavior, which I like to attribute to our genetic relationship. And for that reason, I broach this issue in my journal here.

Kalimohan had gotten interested in the Brahmo Samaj movement, when he was sent by Tagore to Giridi, even before Rabindranath dug his root in Santiniketan. From his family estates in Bangladesh, he had sent a young and ailing Kalimohan to Giridi. Overwork, undernourishment, and a hot and humid environment had combined to enfeeble young Kalimohan, who had succumbed to pleurisy, a form of tuberculoses. Alarmed about Kalimohan’s chance of survival, Tagore had called for an English doctor to visit from a nearby town. The doctor recommended that Kalimohan be transferred for cooler to a drier place. And thus, Rabindranath sent Kalimohan to Giridi. Kalimohan met up with a lot of progressive people of the Brahmo samaj movement there.

What happened after that, is a good example that helps define Kalimohan. He got influenced by the movement because of its main theme – that all humans were equal. This resonated with Kalimohan’s own beliefs which had already been molded by a close association with Tagore in his East Bengal estates. Then, as Rabindranath was released from his duty of overseeing the family estates in East Bengal, he asked and got permission from his own father, Devendranath Tagore, to use the premises in Santiniketan, to form a school. It was then that Rabindranath called Kalimohan over to Santiniketan, and engaged him with the budding rural reconstruction efforts there.

Kalimohan left Giridi for Santiniketan, but carried with him a fondness for the basic premises of the Brahmo Samaj movement.

Kalimohan did not engage in idol worship. This part of his belief was shaped by Tagore when Kalimohan was still in his late teens. Subsequently, no image of any God or Goddess adorned the walls of his mud-walled home in Santiniketan. But other than that, he did not impose any religious do and do not within his home, except for one thing – nobody and nothing, was untouchable. Tribals as well as low caste Hindu, and Muslims and people with any other kind of faith system was not only allowed to visit, they would eat using the same utensils that the rest of the family used, eat the same food, sitting side by side with the family and would use the same water, soap, towel and everything else. All a person required, to find equal treatment in Kalimohan’s home, was to be a human.

This was strictly adhered to. This was not just proving a point, for Kalimohan. This was what he believed in, and he needed to set an example by living it in his own home, before he could go and preach it to others in the rural community around Santiniketan. Lastly, these people, if tired at the end of a long travel, could also sleep over at Kali babu’s place. Again, no segregation on caste, tribe or religion. Women were segregated from men. That was about it.

And he got enlightened to this faith system based on universalism of humanity, directly from Rabindranath Tagore – first hand. This was at a level higher than Hinduism, Brahmo Samaj movement, Islam, Christianity or the pagan faith system used by the Santhals. This is what Tagore meant by faith systems in his book “Religion of Man” although he did not use the words I used here. It is my belief that Kalimohan was likely his first, and perhaps last, convert on this religion. Rabindranaath had a lot of followers and hangers on, but only one true disciple.

Meanwhile, not having idols on his walls was an area where one could identify perhaps an influence of Brahmo Samaj. I have seen comments as well as writings, claiming that Kalimohan had secretly converted to Brahmo Samaj. I dispute it. Kalimohan was not the type of person to change his faith system in secrecy. Besides, Rabindranath’s influence was very strong in Kalimohan’s life. And Rabindranath had long since realized that converting from one religion to another did not solve anything. It only alienated a person from his old social network. There is enough mention by Tagore in his letters to third parties, that he was a bit worried at times, about Kalimohan getting “too” influenced by this or that religious types. This in itself should be a good indication of what Tagore thought of religious zealots. In short, there is a lot more to Kalimohan’s bare walls devoid of deities, than a simplistic answer that he secretly had converted to Brahmo Samaj.

Kalimohan was influenced by Tagore’s humanism first and in a fundamental way, and Brahmo Samaj later, and as a milder interest. None of the erstwhile Brahmo samaj practitioners in Santiniketan or elsewhere went as far as Kalimohan went, in accepting all humans as equal in his own home. That should explain part of Kalimohan’s mid set, and set him apart from the rest even in Santiniketan, barring of course Rabindranath Tagore himself.

So, revisiting the issue of Kalimohan’s attachment to the progressive people in the Brahmo samaj movement in Giridi, he was naturally attracted because their core beliefs tallied with Kalimohan’s own – the most important of them being that all humans were equal. This belief he had absorbed from Rabindranath, and not from Brahmo Samaj. Rabindranath Tagore was very careful in not rubbing any particular brand of his spiritual belief on to others. But Rabiindranath’s own life practices were great examples for Kalimohan. Kalimohan, following his mentor Rabindranath, did not allow his eating or living habits restricted within a narrow religious and caste corridor that made it impossible for people of other faith systems or other castes to exchange views freely. Tagore did not keep a fence between himself and other humans. Kalimohan had dismantled that fence around himself very early in is life, thanks to Rabindranath.

Getting back to Brahmo Samaj, he started visiting Kolkata to attend every annual Brahmo Samaj meeting in January. This is a practice he started when he was brought to Santiniketan by Rabindranath. But, after a few years, Kalimohan stopped going there, and entered a suitable comment in his diary. He was tired of listening to theoretical topics and arguments on finer points of the correct interpretation and definition of God, or the right way of conducting social or religious ceremonies, and other symbolisms and protocols. He was tired of hearing about differences between various fractions of the movement. But most importantly, he only found arguments about methods, theories, definitions and symbols, but did not find discussions about man. The exchanges involved too much description of god and not enough of understanding of man. The universal man of Tagore was missing from the arguments going on in those meetings.

Service for humans and for humanism was the prime religion Kalimohan had learned from Tagore. He did not find it among the Brahmo Samaj people in Kolkata. And therefore, he stopped going there. Did he find that in any other religious groups? I doubt it. He followed a personalized religion that he had inherited from Tagore, and had fine tuned to suit his own perspective on life.

And it is here that I find I share genes with him.

What he found about the Brahmo Samaj, can be multiplied across all the organized faith systems across the world, and I came to a similar conclusion in my own life, about institutionalized religion in general. They were not for me.

But this habit of analyzing what he saw around him, and judging if the practice was meaningful or not – this questioning mind – is an aspect of Kalimohan that I can immediately relate to. I have the same bug that he had. And for that reason alone, this topic of Kalimohan‘s visit to GIridi and his exposure to the Brahmo Samaj movement deserves a mention in my post here.

So, coming back to the issue of writing about my grandfather’s work with rural reconstruction, giving shape to the efforts on the field that Tagore more or less invented in the Indian subcontinent in modern times – nobody really cared to know it.

For that matter, main stream does not care about re-analyzing the socio-cultural situation anywhere, India included. Main stream does not cater to middle class any more. The middle class is not socially conscious any more.

There is however, a growing number of minorities in the western societies that were beginning to realize that our civilization is lopsided and unsustainable. But Tagore’s name had not yet entered into that sphere. Nobody identifies Tagore with socio-economics or sustainability, or environmentalism, or rural reconstruction, or much anything other than writing a few songs. Gandhi’s name was was more readily associated with these things, because of the image he projected through national politics of freedom. Gandhi ran an ashram those days, and did try to address the cast system. But his involvement did not go as deep as Tagore’s had those days, with focus on finding pathways to address the economic disconnect between the rural and urban India, and to also address its class distinction and segregation, apart from all other kinds of walls man was erecting around himself. Gandhi, on the other hand, is a much more salable name today. The ruling families of Indian post independence political world, though hardly Gandhian in philosophy, do find that owning that name provides a convenient billboard for political mileage, and therefore has seen to it that the name endures.

Out of a thousand persons I knew, both from India and the world, I could count the number of people that really cared about sustainability in our civilization, and social justice, or true humanism, or preservation of the environment, in the fingers of my right hand, and still have room left for more.

So, I was not interested to write a book to join the Book writer’s club. I had, in short, become quite cynical about those that write books on Tagore, and those who read them.

Then why do I think about writing anything on the man? The reason, I guess has to do with introspection about myself, and where some of the oddities of my character might have come from.

That I was a bit different from my cousins. The difference came from two factors, I thought. One of them was that our family was the only one of our generation among our relatives, that stayed back in Santiniketan and did our schooling there, excepting for Kukul. Being partial to ourselves, I tend to think this might be about the last generation that could have absorbed a bit of something, about Tagore’s universalism, or his internationalism, or his views on sociology and culture. But I do not feel that confident any more. Anyhow, that was one reason – our growing up in Santiniketan.

The second one was my introspection. And in this, I was mostly alone. I had tried to engage others into discussion on issues that bothered me. I could not see, for example, how India could solve its poverty and illiteracy while still maintaining a healthy population growth, without going into a super-expansion mode which would likely exhaust earth’c capacity to supply material. There was a need to re-think the concept of development. But, no one else shared my views among my old friends from the Santiniketan days. I had to search further, and wider, to find compatible thinking.

I thought, even as a school child, that the world would even run short of fuel, paper, slate, pencil, eraser, and a host of other items before India would catch up with the rest. But no matter how many people I presented this questions to, I never could find one that seemed interested, or bothered about the implication. Many thought it laughable that I should worry about limits to producing paper, or ink, or pencil, or slate, or chalk, or even money to build so many hundreds of new schools every day for ever, just to keep up with the population growth. I was a mere school kid, but these things bothered me, and I found nobody that could give an answer. I could not even find a book that attempted to answer it.That these things bothered me, but did not bother much anybody else, was an indication that I might be a bit odd, compared to the rest.

Recently I have gotten my mitochondrial and Y-chromosome genes analyzed and have been studying the results as well as the subject of genetic analysis itself. I understand a bit more about inherited traits and self developed ones.

Then it occurred to me that I was not the only one given to introspection of this nature. My father did too. More importantly, my mother did this, and very frequently in her later years. Also, she was given to write her thoughts in her diary, including poems. So, it seemed logical that I must have inherited this from both of my parents, but primarily from my mother, since the channels of her thoughts often were very similar to my own. They often related to socio-economic issues, knowingly or unknowingly, and to ponder the meaning of existence and so on.

And where could she have inherited these traits from ? Were they mere mutations that manifested only in her and on me? Or were they prevalent in my Grand father too, and also perhaps go back further into the past. I knew a few things that applied to all three of us. These where :

1) An inclination towards deep introspection – mostly relating to making sense of the life and time around us.

2) A deep rooted realization that Tagore should not be remembered primarily as a poet, even if he was a poet par excellence. He was a humanist first and not divorced from reality. His reality, however, was deeper and not superficial.

3) All three were not too strongly attached to institutionalized religion, and believed, in our own ways, that the best path for humans is to find an equitable and balanced way to live without degrading his neighbourhood.

All of them were essentially lonely, and not very well understood by those close to them.

From these, I had suspected that there is something in our genes, that perhaps my mother got from him, and passed some of it to me. It did not come from mitochondria, because he did not pass that on to his kids. It could not be a direct copy of the Y-chromosome because he did not pass that either, to his daughter. And yet, I have inherited, I feel certain, in some fashion, a bundle of genes somewhere, from my grandfather. Perhaps it is partially mixed with that of my father. But somewhere, in some chromosome, I have a bit of a protein or an amino acid, that somehow prompts special sets of neurons to fire in my brain at odd times, and turns me into an oddity among my relatives.

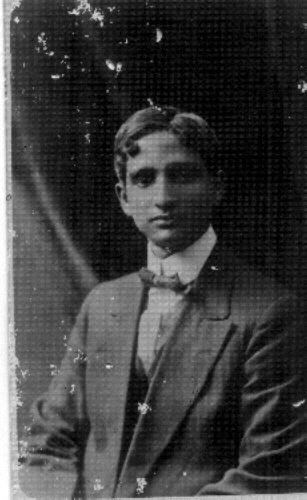

And I do no even have a good picture of my grand father.

The above is one where he was sent to England when he was a mere twenty year old young man. The reason he was sent is in itself a bit strange. Tagore has written here and there about Kalimohan. But one of the reasons had to do with the British India Police. My grandfather, before he came to know Tagore, was engaged as a teenager in some freedom movement, giving lectures here and there about the need to organize and strive to get the British to leave India. Somewhere there, his name got into the police records. Meanwhile, having met Tagore, he had already realized that pushing out the British was the least of the problems facing India. The root cause was a weakness of the social foundation that made it possible for British or others to rule India. This foundation was rotten and falling apart, and needed to be re-strengthened from the ground up. That was a very difficult task, and there is no good roadmap available. One would have to find ways and improvise and solve problems that came up. It was going to take many lifetimes of work, and it would be a thankless task. But that was what was needed, for improving the real lot for India.

My grandfather was the first of Tagore’s converts. He remained the most dedicated to it, till his death.

Tagore sent him to England to throw the police off his scent. Whoever went to England to study anything, always returned as an Anglicized babu that was fully converted to believe in the British system and its suitability for India. These people never became freedom fighters. And so, the Police would leave them alone. This was the policy being followed that time.

History would eventually prove this policy wrong. Tagore himself had studied in England, as had Gandhi, and Subhash Bose. None of them wanted perpetual rule of Pax Britannica. But that was in the future. The British Police did not know about Gandhi at the time, who was many years away from entering Indian politics. Subhash Bose was a mere toddler at the time.

And so, my grandfather, wearing a most unusual dress for him, in suit and wearing a bow tie, got himself photographed somewhere, and a copy of it ended up with me.

But I am not ready for Kalimohan yet. I am still not through with my introspection about my character traits and its failings.

I had always had two sides of myself. One one side, I liked hanging out out with people. This was the more prevalent trait in my youth. Perhaps I even dominated conversations with friends to some extent, while also being the source of generating fun and a lot of entertainment for everyone. I do not know where I got it from, but I can trace parts of it in my father as well as some of my maternal uncles. But, even in my youth, I displayed a separate trait that set me aside from my friends and relatives – about introspection.

That side of me was pensive, analytical and often wished to go deep rather than stay at the surface. A lack of clarity into the depths and a shortage of information or people that liked to engage in such topics was a source of both frustration, and disappointment for me.

This pensive side wished to put everything I saw or felt, into a process of analysis, study and examination. There was also a creative side, that might express itself in writings or sketches or even a poem or two, in Bengali or in English. This side required me to spend time by myself. This side also made me into an avid book reader. I was fortunate enough to be self sufficient at an early age, and could afford to buy an unending stream of books throughout my adult life. I do not have a clar tally, but must have bought more than a thousand books that had no direct bearing to my profession. There was almost no subject that I was not interested in. I read all the major religious books around before deciding that I was not very religious. I read Karl Marx’s Das Kapital as well as Mao’s book, before concluding that communism as practiced was not for me. It took me many years and absorbing many more books, podcasts, essays, papers, and TV interviews as well as constant introspection and watching the world with my eyes, and thinking things over, before it dawned on me that the western civilization was bankrupt and unsustainable, not only because it was consuming faster than the planet could provide, but also because the philosophy itself was on weak foundation. In other words, there was no civilization that I knew of, of historical times, from any part of the globe, that could provide the answer of running a perpetual machine.

I often ended up on introspection on how I might have engaged Tagore on some of the issues that was clearly close to his mind. One of them was what he wrote at the end of this life, as the world entered its second world war. He stated that he had lost faith on every human institution, but never lost faith in man. He believed that man would emerge victorious, and would eradicate the maladies and distortions that the human institutions impose on each other.

I would have liked to challenge Tagore, had I been his contemporary, on this notion. I know it is absurd. If I was born in his times, I would not have had the privilege of seeing what the western civilization was capable of doing. I would not have had the time to introspect on the two sides of the expanding Indian diaspora around the globe. This overseas Indians represented a success story on one side of the coin. The Indians themselves are so full of it that it is beginning to inflate their brain, I suspect. The other side of the coin is their extreme apathy and inability to understand even the basics of justice and equity. Talking to some of these “success stories” is like talking to an imaginary Martian.

Anyhow, I would have argued with Tagore even on his own comment. How could he lose faith in human institutions and not on man, since men created all those institutions and men operated them. I know he would likely have mentioned that, for him, the “man” was not among the exalted class. He was not from the political, or social or economic, or academic elite. Man, was to emerge from the masses. In those sentiments, Tagore was a Marxist in some ways. And I would have argued him to the end of the day about this conception. I did not think anybody coming from the masses was any less selfish than others. I could rattle off a long series of bad men that came from the ranks and went berserk once they got entry into the corridors of power.

I would have argued with him, historical era by era starting with the first time man invented fire, to the first time he invented agriculture, produced metals, manufactured paper, to when he found coal, invented electricity, all the way to the present. Tagore died four years before Hiroshima. He had no idea what man was capable of doing, all of which negative in a way.

Anyhow, that is just a day-dream. Tagore is not here, and I was not there. I doubt I would have had the personality to engage Tagore into any serious discussion where I disagreed with him. I know Tagore was very bitter about human civilization, and about the Indian middle class by the time he was in the last year of his life. I became bitter about human civilization while I was middle aged. And I got access to reading material far in excess of what was possible in Tagore’s times. I have taken full advantage of it, and do believe have read more books on more topics than even existed in his days.

But he had a very great advantage over me. He had personally met, and discussed with, almost the entire worlds intelligentsia, from the east, to the west, north and south. There were so many famous people he had met and exchanged views with, that it might be a fair statement that there was just nobody, in the west or in the east, that could boast of that kind of a wide circle of acquaintance. Mine in comparison is – so insignificant that it could not compare at all.

But the results have been largely same. He was disappointed in human civilization because he had pinned high hopes on them and they came up short.

I too was disappointed. I could see every civilization at the end of the day suffering from an identical malady – inability to see what is obvious to an outsider – that their system is bankrupt and heading towards a collapse.

I could also see that the procession of civilizations was not perpetually cyclical like the dance of the Hindu God Nataraja. There would be a point where a civilization would go, and another would not replace it. I could clearly see, that we had reached that point. There was not going to be another civilization greater than this one. And this one was doomed.

I would have tried my damndest to make Tagore see my point of view.

But, the issue here is not Tagore, but my grandfather.

I have no idea where his thoughts roamed. But I could see that he was a lonely man. His close relatives did not speak with him except for mundane family issues. My own mother was in her early teens, and not yet an adult.

Tagore was a generation older and busy with so many other things. Kalimohan often spent time smoking his hookah and contemplating by himself, writing his diary and meeting people. He exchanged some of his views more freely with people that were not close to him – such as villagers and folks that came to see him.

In this, he shares a common trait with both my mother and myself. My mother had remained lonely throughout her life. Those close to her did not understand her well. She was not even very easy to get along with. And she introspected on topics others did not even think about. She had a very strong sense of right and wrong, and very low tolerance of dishonesty.

I have inherited some of those traits too but with some moderation. I do not go berserk if I see a dishonest person. That is because I have been exposed to so much of it, thanks to an advanced lifestyle than my mothers simple one. She had the advantage of not having to deal with too many crooks.

Both Kalimohan and my mother knew loads and loads of people – many of them very important. And yet, both of them were very lonely in their personal life, in spite of having so many relatives.

And I am subject to the same set of conditions.

I do not believe this is an accident, or an act of God. Besides, I do not really believe in God anyway. The reason for this must be my own behavior or character. Likewise, my mother was mostly lonely because of her oddity, or her individuality. Same, I suspect, was the case with Kalimohan.

More I thought about it, more I came to conclude that, without knowing which sequence of the gene it might be, I have inherited some of my grand father’s traits, through my mother. In that, I can now feel a bond with the man.

I have never been involved with anything where any police should want to keep a tab on me. But that does not mean I am a better person. It just means that I was born in a politically independent India and did not have to push the British out.

I did not go to England for easy studies, although I did end up there later for a few months for some study, and found it rather easy to pass those exams compared to the standard in india on those topics.

There were other differences in the life of each of us. But in general, we were so very similar.

This side of me was not properly understood by my friends and relatives, and went largely unnoticed.

I was likely heading for the same realization that my grand father had – being bitter about the mean and petty minded ness of his contemporaries in Santiniketan. He was so fed up with it that he tendered his resignation to Tagore, which Tagore tore up and refused to accept. I had seen Tagore’s written response to Kalimohan on this issue.

I had read my own mothers posts and had heard her speaking with me about her disappointment about life and about people around her, in Santiniketan, in the local and national Government and elsewhere.

And then I have myself.

Thinking about it all, it came upon me that, I might have some insight into Kalimohan the man, even if I had never met him, even if I was born a decade after his passed away.

And here, you have the first installment of that effort, written off the cuff and more as an introspection in itself.