Lately, I have been changing my interface with social networking sites on internet – by reducing my presence in Facebook and increasing it in google plus.

Facebook was getting to be a bit addictive and I decided to cut the addiction. It was also taking more of my shrinking slice of personal time. I concluded that the time spent on Facebook was more wasteful than productive. And after having quit smoking, I felt confident of kicking any bad habit.

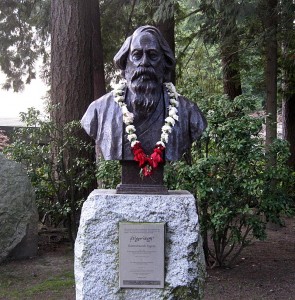

We are creatures of habit, and develop attachments through our lives. Our growing years have a lot of influence over our thinking and world view. It is without a doubt, that Rabindranath Tagore played a very big role in my world view, even more than Gandhi or anybody else did, barring my own parents.

But – I grew up. I matured. I acquired the ability to attempt to think independently and to step outside the proverbial box in order to do so. And as I matured, rather late in my life, I realized the need to divorce myself from some preconceived wrong notions. These included keeping Tagore welded to junk heaps of of sentimental dead matter.

Tagore needed to be freed from Santiniketan. He needed to be set free from Bengal. He needed to be unshackled from the cult of Tagore.

Tagore was many things, but not a cult figure whose mantra needed to be chanted mindlessly by the masses in the hope of achieving some fictitious nirvana. But, the masses will do what it will. I needed to set myself free from that grotesque caricature.

Tagore had written “Tasher Desh”, the land of cards. It was a great social parody with a serious underlying message. The land of cards needed to rid itself from millennial accumulation of dead habits and debris. Fresh air needed to course through their land and their lives. A prince charming came from a far off land and set them free. Rules that no more served a purpose other than mindless copying of meaningless tradition, needed to be broken. Habits that were locked in stone and unable to evolve needed to be changed so creative freedom could again express itself.

Ironically, Santiniketan had turned itself into another Tasher Desh – a land of cards. It had become moribund, devoid of new ideas or creativity. The cult had barricaded itself with mindless copy of Tagore’s words, like the parrot in Tagore’s own satire – “Tota Kahini” the Story of the parrot. Santiniketan took to repeating ceremonially repeating Tagore’s words without understanding or believing in them. They did not promote Tagore’s vision by application of it in their actions and endeavors. Instead, they killed Tagore by parroting him incessantly, by turning him into a framed picture on the wall, a figurine to sell in Poush Mela. They ended up reducing his legacy to a mere creator of some music and dance for the weekend amusement of a group of hapless Bengali babus.

The cult represented a slow degeneration of ideals and values. Tagore the universal man was unrecognizable if one limits himself to watching Santiniketan, and the hordes of Tagore lovers sprinting all across the globe busy promoting themselves.

Santiniketan became a den for misfit leftists, dimwit academics, useless nincompoops that had no love for either the land or the people, and were merely there to fatten their pockets and live a lazy life without working. They ensured more and more useless folks accumulated there, supporting each other – so that the place was thence unsuitable and hostile for anyone with a wish to break the deadlock and inject some life into the comatose patient.

Outside of Santiniketan, the greater Bengal, in its own path of slow decay, provided a suitable backdrop. The culture and the cult has now gone virtually underground. It is not underground in a legal sense. It is not hiding from law. Its only crime is uselessness and failing to to display sign of life, energy, honesty or vitality. Thus, it has sunk below the radar of the living world.

Santiniketan does not exist for the rest of the world, and for good reason. It is hardly a place for bright, honest, free thinking, progressive hard working representative of humankind whose vision goes further than the tip of his nose. Shyamali Khastgir might have been the last free spirit to percolate through the dead leaves heaped at the bottom of that decaying forest.

It took me a lifetime to realize I was getting supersaturated in this foul broth. My parents provided a buffer. They carried with them a breath of the past long vanished on the ground, but still surviving in the minds of the older generation – of simple living and high thinking.

But my parents are no more.

Today, we have a lifestyle of high living, dishonestly at the taxpayers expense, giving nothing in return. And instead of high thinking – there is no thinking. Cognitive activity is too taxing for the brain. It has been sleeping for two generations. It has lost the will to wake up and get to work. ঘুমে জাগরণে মিশি একাকার নিশিদিবসে।

With my parents passing, I was, late in my life, forced to peer outside the cocoon and look at the Tagorean world as it exists now. My extended childhood was over. I had to now confront the legacy of Tagore from my own perspective and look at it through clear glass of reality. I had to confront the unenviable influence of the cult of Tagore in denigrating the image of one of the greatest social thinkers and universal philosopher that the world had seen.

I could see I was soaked with this unhealthy odor emanating from the gathering mass of pseudo devotees of this new cult of Tagore. I was surrounded by mindless cult followers, stifling my air and blotting my sky. Half of these devotees wanted only to further their own little careers while using what was left of Tagore’s carcass as a stepping stone, while the other half lacked cognitive ability to think through anything, let alone analyze the intricacies of life, real value of Tagore’s visions or how these could be applied to an ever changing humanity and planet.

My social networking environment had been filling up a this slow stench of decay and a large crowd of nonplussed groupies under a Tagorean banner, that did not really share any of my views on anything. I was surrounded by people in denial.

This is not an uncommon state. Americans are in a state of denial about their decline. Western economic model is in a state of denial about its un-sustainability. The petrochemical industry and the governments they support are in denial about the end of cheap oil, religious nuts and the public in general are in denial about the threat of overpopulation. Everybody is in denial about the great mass extinction of species going on right now. Bengalis are in denial of the existential threat to their language and culture and the steady decline of Bengali thinking. So I guess Tagore cultists are no exception. My mistake was in expecting them to be any different.

Soon after the death of my parents, I started getting increasingly skeptical about the intention and the ability of hordes of ladder climbing Tagore worshipers sprinkled around the world. I needed to synchronize my views to match reality. In reality, Tagore and Santiniketan had already divorced each other a long time ago. It was therefore unfair to continue to keep Tagore’s coffin buried in the desert sands of Santiniketan. Santiniketan has to either stand on its own, or be buried by the sands of time. It had been conceived and nurtured by Tagore in its infancy. But that was a long time ago. Santiniketan had long since grown up as an adult, and has been charting its own course for a few generations. It needed to face the world on its own terms and on its own two feet, without support. If it was top heavy with weak legs, unable to support itself, it would need exercise. Giving it a pair of crutches bearing Tagore’s name would only lengthen its misery.

It took me a while to realize that in this new scenario, I needed neither Santiniketan’s residents, nor its ex-students to expand my understanding of Tagore. There was nobody left there that could add anything other than their own little agenda. Remembering the life and times of Leonard Elmhirst, I recalled how he, later in his life and much after Tagore’s death, appeared to be thoroughly disenchanted with Santiniketan. Was there a common link in all this ? I know my uncle Salil Ghosh had a long association and correspondence with Elmhirst, but the content is unknown to me. Unfortunately, I did not think of all this while Salil Ghosh was still alive.

Anyhow, looking around for a hangout, I concluded that there was no need for me to even contemplate a hangout on Tagore. The kind of folks that might drop in are the very group Tagore needed distance from.

There was of course another reason for tilting towards Google plus. It had its advantages. My first impression of the place was, I was able to find more folks that followed my line of thinking.

Say – wild life watching. There were not many that shared my hobby and interest within Facebook. Perhaps that could be amended. But here in Google, I found it easy.

Then – archaeology, anthropology, geology, sustainability, climate change, nature and wildlife preservation, globalization, financial crisis, plight of the aboriginal people, over-mechanization of industry and exploitation of the rural environment. I could hang out in specific hangouts, or create my own.

Are these things related to Tagore? Well, ask a Santiniketanite that is busy singing ‘Amader Santiniketan’ noon and night, and he might not find any relation. That’s because the cult of Tagore only learn to chant mindlessly and without comprehension, but not the application of the formulae in real life – which was the primary goal of Tagore for creating those verses, music, function and events in the first place.

In Tagore’s own mind, there was more life that needed living outside of sanctified temple-altars than inside. Of course there is elements of the Tagore’s vision in Universalism, in climate conservation, in activism to protect our forests and the lands, watching and appreciation of nature, sustainability, tribal life or the exploitation of our villages. These are the issues with which a younger Tagore would have loved to get his hands dirty, and an older Tagore would have pushed and cajoled the younger generation to get their hands dirty. Tagore’s visions were to be fulfilled in the outside world through appropriate karma yoga, and for a continuous re-thinking and striving for betterment of an equitable society in harmony with its natural environment. His vision was not to be fulfilled in walled zoos packed with robotic people programmed to parrot out Tagore music and functions periodically for paying tourists.

As I think through the life of Tagore and his efforts with humankind, both in India, and in the easter civilizations as well as the west, I can conclude with some hope, that Tagore would survive because he represented a path that was universal culturally, ecologically, economically, sustainably and equitably. It was vision that never claimed to be perfect, but always encouraged questioning minds to forever strive to tweak and fine tune. It was a vision and a blueprint that is as relevant today as was in his time. Santiniketan, meanwhile, stopped representing Tagore, or sustainability, sociocultural creativity, or universalism or anything at all that could be worthwhile for humanity. In Tagore’s original blueprint, the place and the institution, along with its ever increasing number of ex-students were to spearhead in a lot of directions to find creative and unique solutions to new challenges that faced humanity – solutions that were not a mindless copy of either the west or the eastern past. Solutions that promoted an equitable relationship between the city and the village, between the affluent and the not so affluent, and between people of different race, cast, religion and cultures.

Today, Santiniketan is so far behind on all the sociocultural issues of today, that nobody looks up to the place to provide any answer to anything anymore. Santiniketan therefore, needs to engage in fresh soul searching to identify a reason for its existence.

Rabindranath Tagore meanwhile deserves to survive outside of Santiniketan, outside of tepid academic debates, and power-point presentations on the screen in quiet auditoriums. He needs sunshine. He needs freedom from the clutches the Tagorean cultists. He deserves to be among the people of this planet, and not sterilized, myopic pundits and blind groupies.

And so – be well, Cult of Tagore. It was nice knowing you.