A world without bee eaters?

The golden age of Bengal is behind us. What is ahead of us – for Bengal, India and in fact the rest of the world – is uncertain bordering on gloomy. We are, without a doubt in the midst of the sixth mass extinction. Over 90 percent of living flora and fauna are on the way to extinction – thanks to human civilization and DGP growth.

I do not see hope in a horizon dominated by sky scrapers, our paths dominated by automobiles and our society sprinkled with politicians that betray their constituents and advanced nations ruled by warlords.

I do not see hope in a horizon dominated by sky scrapers, our paths dominated by automobiles and our society sprinkled with politicians that betray their constituents and advanced nations ruled by warlords.

And yet, man learns to hope.

In the small periscope of my personal viewpoint as I tiptoe past edges of this planet, leaving near invisible tracks on the quicksands of time, I feel telltale sighs of man’s struggle against himself, trying to resist an ecological tsunami brought about by his own kind, couched as progress and development.

My story of addressing glyphosate at a personal level merges with groups of people very different from me and yet identical to me, across the world, each trying their best to push back against this civilizational catastrophe whose root cause might be man’s own destructive genes. Perhaps it is in the formula of evolutionary success.

Perhaps it is in the mitochondrial DNA that we might have inherited from the microbial world and could not genetically digest properly. Perhaps this is what the old sages meant – about creation being the flip side of destruction and that the universe is forever is a duel dance of creation and destruction.

Perhaps it is in the mitochondrial DNA that we might have inherited from the microbial world and could not genetically digest properly. Perhaps this is what the old sages meant – about creation being the flip side of destruction and that the universe is forever is a duel dance of creation and destruction.

I came to India, my birth place, to sell a property. As luck would have it, this took a lot of time. One thing led to another, and I ended up talking to people about my story about Glyphosate. This is a story of my consciousness about the ravages of human civilization. This realization was honed and focussed through help from a handful of North American scientists, and then partially fulfilled through my single handed efforts against almost a thousand elected politicians of Canada.

I had already turned a non-believer of raising awareness. I had lost faith in speaking with people. I had come to believe that – should there is a need to do something to help the society, one should try to do what one can by one’s own self, without ever expecting anybody to help. There is no value in trying to muster public support, or raising awareness. People thus made aware simply take selfie pictures with you, clap hands, and go back to sleep. Therefore, if I am driven by wanting to do something, I either do it myself, or it wont get done.

I had already turned a non-believer of raising awareness. I had lost faith in speaking with people. I had come to believe that – should there is a need to do something to help the society, one should try to do what one can by one’s own self, without ever expecting anybody to help. There is no value in trying to muster public support, or raising awareness. People thus made aware simply take selfie pictures with you, clap hands, and go back to sleep. Therefore, if I am driven by wanting to do something, I either do it myself, or it wont get done.

I was through talking to people and raising awareness. Been there, done that.

But then, I came to India – a world very different from Canada where I live, or USA where I used to live. This is a world where nature is still nature here and there. Where man is busy destroying gaia and gaisa is trying to wrench it back from man.

Earth walled farm house of Bhairab Saini

It is a world where, in pockets of rural India, cattle egrets still follow cattle. Grasshoppers still jump out of the ground, and the morning mist is not carrying particles of neonicotinoid insecticide. Sweet smell of death is not in the air.

A world where bee are still around, and one can still find a bee eater on a twig.

A world where bee are still around, and one can still find a bee eater on a twig.

I have seen bee eaters often enough, but this may be the first time I am contemplating the possibility of a world without bee eaters – for the matter a world without tigers, rhinoceros, lions, giraffe, cheetah, gorilla, hyena, and yes – a world without man, the most catalytic biological weapon of mass destruction ever evolved out of this planet.

Cattle egret following cattle

I never imagined in my wildest dreams that I might one day write a book, let alone a reference book on glyphosate in food. I also never imagined I might write another in plain text, in a language that is not my mother-tongue, a tale of a lonely activist.

But here I am – part of small pockets of people, being washed away by the human civilizational tsunami, and yet pretending to dream of building a seawall to stop this ecological juggernaut whose root may be in my very genes.

But here I am – part of small pockets of people, being washed away by the human civilizational tsunami, and yet pretending to dream of building a seawall to stop this ecological juggernaut whose root may be in my very genes.

I have decided to add a chapter in my book about this glimpse of rural India. I may use the title – Village Panchal, for this chapter. It should have room for the jewels of folk rice conservation – from Anupam Paul to Bhairab Saini and others that I came to know of and appreciate.

But it would also have room for the scaly breasted munia that landed on a piece of dried cow dung not far from me to allow me a few seconds to take a close up portrait. It would have room not only for the bee-eater in the forest, but also the white mushroom that the termites harvest in their termite hills, the civet cats that roam the land at night, and where domestic chicken range free all through the day, pecking at insects that have not gone extinct yet. There are some miniature chickens that move day and night around the ground, and at nightfall, they need not always return to their pen. They just go to the nearest bush and hunker down. They are often taken there by foxes, but that is there style. I saw a few moving around both in day time and at night under an electric light. I should be writing about all this – not just from this village, but also of other villages I visited, other efforts I saw, in other districts of Bengal.

But it would also have room for the scaly breasted munia that landed on a piece of dried cow dung not far from me to allow me a few seconds to take a close up portrait. It would have room not only for the bee-eater in the forest, but also the white mushroom that the termites harvest in their termite hills, the civet cats that roam the land at night, and where domestic chicken range free all through the day, pecking at insects that have not gone extinct yet. There are some miniature chickens that move day and night around the ground, and at nightfall, they need not always return to their pen. They just go to the nearest bush and hunker down. They are often taken there by foxes, but that is there style. I saw a few moving around both in day time and at night under an electric light. I should be writing about all this – not just from this village, but also of other villages I visited, other efforts I saw, in other districts of Bengal.

Free range rooster – GMO free, antibiotic free an chemical free

I saw quite a few majestic looking roosters walking all over the place. Not a single one of them are fed industrial GMO feed, not a single capsule of injection of any antibiotic.

Bengal is not dead. Not yet at least. In fact, Bengal might be leading the nation in some ways relating to propagation organic of folk rice. This too might be a story that has not yet been told.

Home of a cow-owner and milk supplier. He has never heard of either bovine growth hormone, or synthetic milk to add and contaminate his milk. The cows, just like the chicken and goats, eat local foliage. Things are not 100% organic because some herbicides and pesticides are used by those that are not growing organic rice or organic vegetable. Effort is on – to change that.

I would mention the topic of farmers that are trying to bring back cultivation of heirloom folk rice varieties, grown without an ounce of industrial chemical of any kind, but are still not all saving their seeds nor exchanging them. I am increasingly conscious that seed corporations sell or pass around seed packages where neonicotinoids are used.

I have first hand information from fringe villages of tribal people that have not been taught to save their seeds and each starving family still spends several thousand Rupee every year to buy fresh rice seeds in paddy season.

All that brings me back to this bee-eater. Are we heading for a world without bee-eaters?

Villagers offer me an earthen cup of tea, welcoming me to Panchal, and refused to take money.

I saw in Panchal what I had been told by many, about conservation work in maintaining unique characters of various indigenous rice strains, without allowing the diversity from dilution through cross pollination. Rice flowers are air pollinated. What this means is, if one is trying to grow ten kinds of rice in a congested piece of land, then there is always the chance that one pollen from one kind of rice will pollinate another kind growing very near it, thus crossbreeding and losing the originality of the second kind. In order to prevent that, farmer use various techniques. Here we see one technique, where groups of plants flower at different times, so that when one is pollinating, nearby rice strains are not. Some farmers even wrap up some of the plants with some kind of shield so that the clusters self pollinate themselves but do not affect nearby varieties.

Examples of timed pollination, where one kind of producing getting ready to flower while nearby varieties are not yet ready.

Either way – I am likely to add a chapter – titled Village Panchal, in my book, and include the story not just of Panchal, but also of Northern Dinajpur and Purulia, covering the efforts and aspirations of small pockets of people trying to push back as this toxic juggernaut in a death-struggle with gaia, the living planet, like a serpent and a mongoose grabbing and tearing each other to pieces in a fight to the finish that ensure mutual destruction. The living planet will be finished. So will man.

The story of the Dhoincha plant.

There are many stories within stories here. One such has to do with complimentary plants, recycling of soil nutrients, nitrogen fixing and the role of the “Dhoincha” (ধইঞ্চা or ধঞ্চে) plant, a member of the Sesbania family. I believe this family, or at least some species of this family, are considered to me leguminous and are able to “fix nitrogen” in the soil. They are also considered kind of complimentary to paddy. One neutralizes the effect of the other, and tries to leave the soil as close to original with regard to nutrient content and soil health, as possible.

Farmer Bhairab Saini, his kid son and his grown up nephew are keeping track of the folk rice, standing right next to a Dhoincha plant in the middle of his folk rice conservation field.

Debal Deb tells us the correct scientific name for the Doincha plant to be Sesbania cannabina. Some mere mortals believed its name could have been Sesbania aculeata. I personally don’t care if it is renamed Sesbania Dhutterika (শেষ বানিয়া ধুত্তেরিকা). What is interesting is that farmers that may not know of the existence of latin as a language, or the world’s decision to use latin words to describe every living thing on a scientific platform, might nonetheless have figured out by themselves that Dhoincha is a good complimentary plant to have with paddy. Some useful nutrients that rice pulls out of the ground – are recycled back in the soil, by this Dhoincha. Its root systems, for some bio-molecular mystery I am personally not educated enough to explain, encourages symbiosis with groups of microbes that form tiny nodule-colonies along its roots, and helps do the nitrogen-fixing.

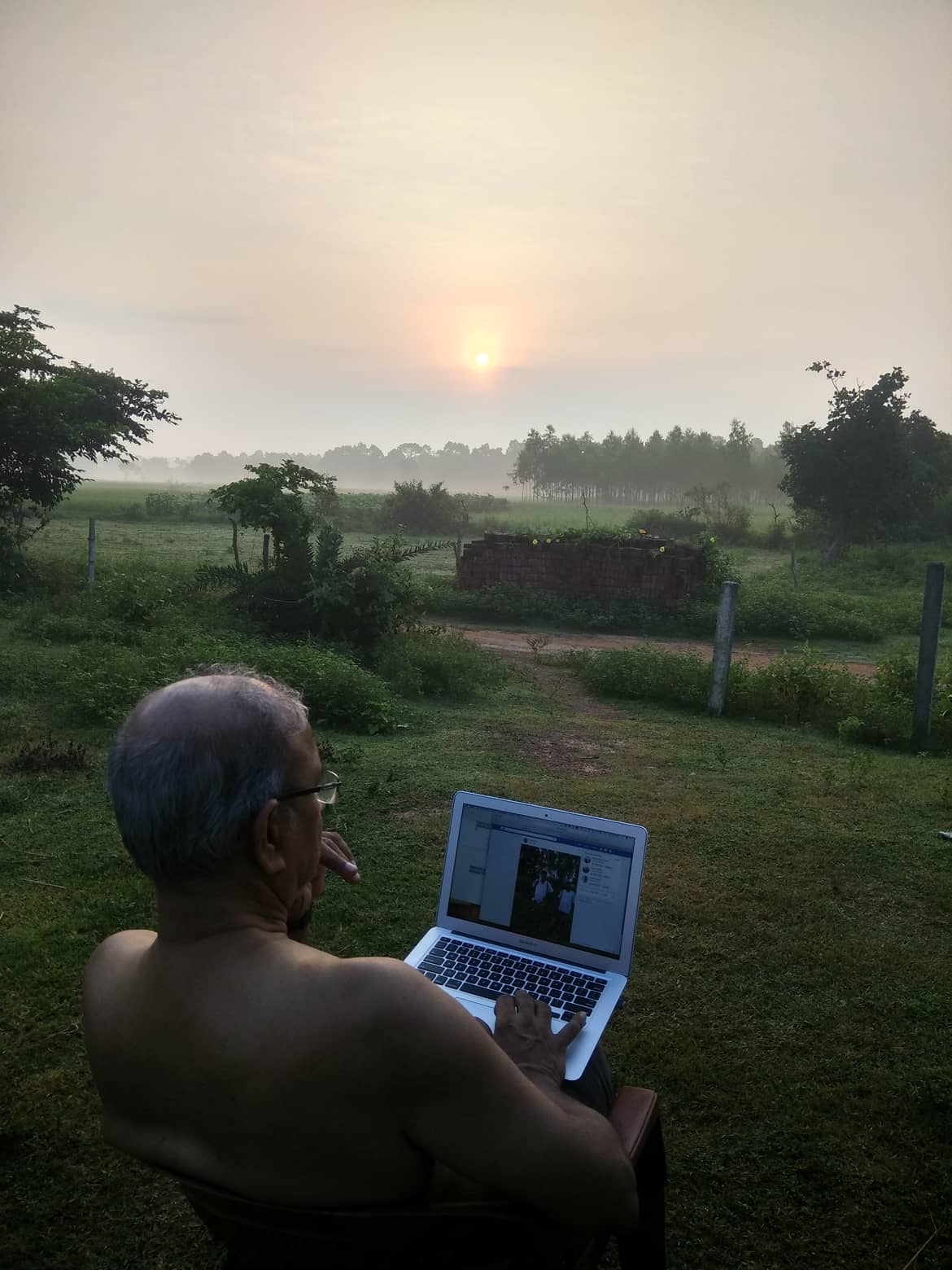

Sunrise – Panchal, Bankura. Myself with my laptop. Picture clicked by Rajib Mukherjee

What is nitrogen fixing anyway ? Well well. Nitrogen is plentiful and inert, in our atmosphere. A compound of nitrogen is ammonia. Ammonia and other compounds like these are the sources for construction of more important organic molecules that from the basic building blocks of all proteins, or all life forms on earth. Therefore, ammonia can be considered a key chemical element that needs to be in the correct form, in the soil, for plants to pick up. And once plants pick them up, presence of that form of nitrogen compound reduces in the soil. This also applies for all other nutrients that a plant picks up.

Checking rice conservation and identification details – Rajiv Mukherjee, Bhairab Saini, Arun Ram and Bhairab’s nephew.

Nitrogen-fixing means putting those compounds of nitrogen back into the soil after a particular agricultural crop has picked most of it up through its harvest. This nitrogen-fixing recycles the depleted nutrient back in the soil and prepares the ground for replanting of the same crop, again and again. If recycling of nutrient cannot be done naturally, then the soil becomes infertile. Industrial agriculture model then tries to sell synthetic fertilizer to pump select nutrients back in the soil, keeping the soil alive through life support, for a longer period.

Speaking before Panchal villagers about dangers of using glyphosate.

Dhoincha, through the microbial symbiosis, helps in nitrogen-fixing and by allowing it to rot back into the soil replaces some carbonaceous matter back as well.

By the Shiva Temple, villagers sit down to hear about glyphosate

The plant has other interesting features too. During the early phase of growing folk rice without pesticides or herbicides, the fields may get infested with insects wanting to eat some of the growing rice seedlings. These days, when killer chemicals are so readily used everywhere, the insect kingdom has a shrinking field where they can still exist. They too are parts of the great symbiosis of this living planet. So they naturally congregate towards those pockets, where killer chemicals are still absent. There may, as a result, be an overcrowding of rice seed eating insects.

Dhoincha plant provides convenient perch for insect eating birds like the drongo. This is a good way for balancing things out while supporting the biodiversity of the land. This is what the Dhoincha plant also does. However, there is.a down side to it too – as Abha Chakraborti informed me. Once the rice seeds begin to mature, serious seed eating finches such as the Baya or weaver bird might congregate and gorge themselves on rice. Providing them a perch from the Dhoincha plant might turn counter productive. Therefore, when the seeds start maturing, the right thing to do for the farmers is to uproot the Dhoincha, and lay it on the ground right in the middle of the paddy field, and let nature do its work. Next season, another Dhoincha is planted again. There is a way healthy clean food such as rice can be grown without killing everything off, and without poisoning us. These Bengal farmers are showing me how it is done.

Sunset at Panchal, Bankura, West Bengal, India.

Folk rice conserving jewels of bengal

There has to be a story inside a story inside a story – like the Mahabharata – epic of Indian mythology.

There has to be a story inside a story inside a story – like the Mahabharata – epic of Indian mythology.

I have posted a version of this picture before – but believe it deserves some description.

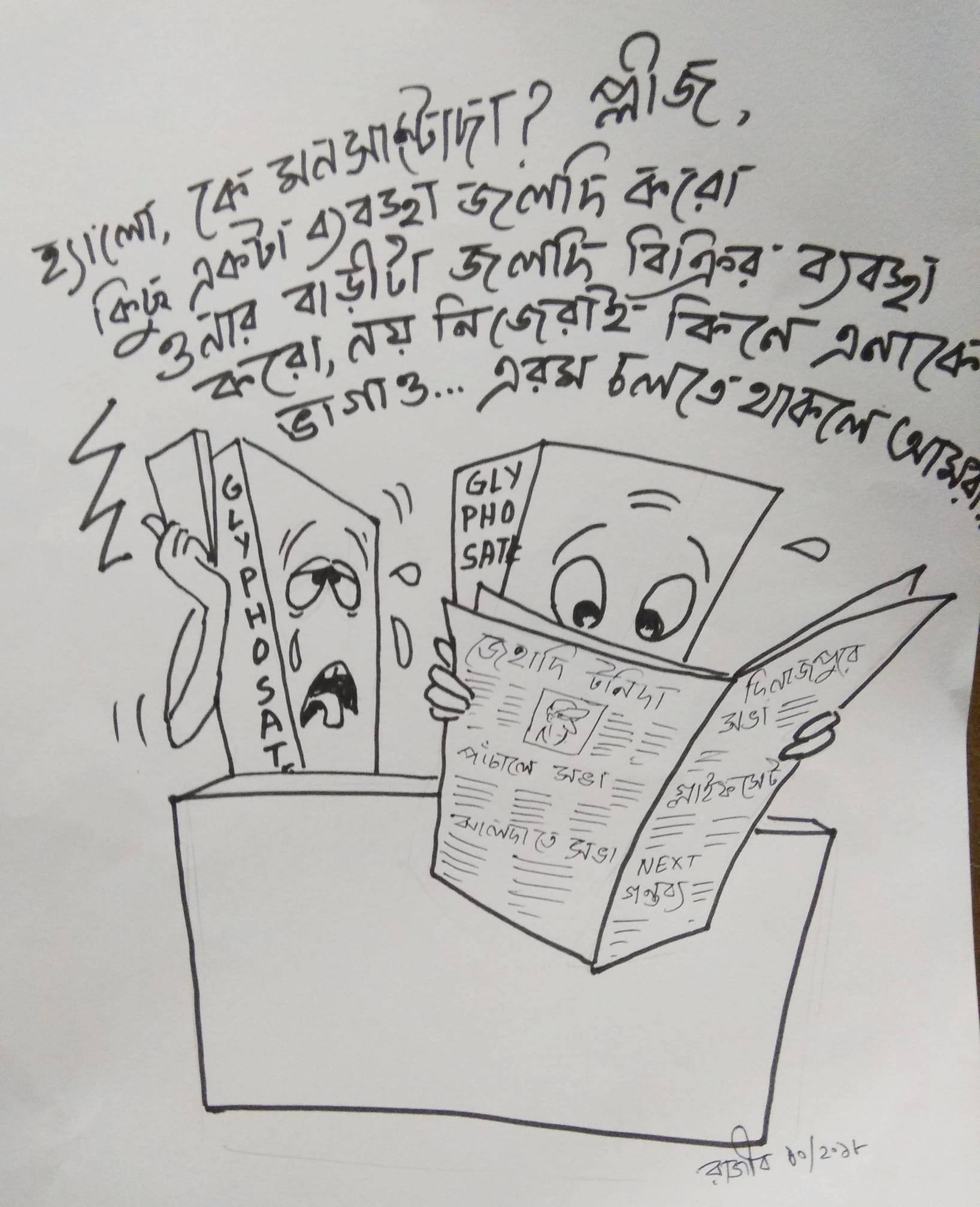

At left is – Rajib Mukherjee. He travelled far, from Asansol. He planned to come all this way on his motorcycle, but it broke down I front of his home. Nonetheless, he came by changing buses. He said he was coming to see me, but I suspect he came to meet all of us, especially the organic folk rice growing legends. Rajib has a few distinctions. He reads a lot of interesting non-fiction. He had already read James Lovelock’s Revenge of Gaia. Then, while listening to me, he ordered 1) Poison Spring, by EG Vallianatos (about extreme corruption of US-EPA) and 2) Value of Nothing, by Raj Patel (about cost of environmental damage incurred by production of common industrially mass produced items like a hamburger). Clearly, he reads serious books, and that sets him apart from 99.9999% of the rest of humanity. There is another distinction for him. He also draws cartoons. I was wondering if he was going to draw this particular nava-ratna (nine jewels). Instead, he drew a cartoon involving me.

Glyphosate packets are complaining about me to their boss Mr. Monsanto, and imploring him to see to it that my property is sold pronto so that I can return to Canada and leave them (glyphosate packages) alone.

The story of the cartoon goes like this – I originally came to India to sell a property – which is taking time. As a result, I am using that time to talk about glyphosate. With that background, this cartoon is make, where a few characters called Glyphosate are calling their boss, a character called Monsanto, over the phone, and imploring the boss to personally see to it that Tony Mitra manages to sell the property soon – and leaves India. If needed, the boss should buy the damned property himself, to ensure Tony Mitra is gone. Else, life is going to get increasingly tough for glyphosate.

Pair of Indian silver bills

Next – Mr. Arun Ram.

He too has an unique distinction. He came upon the idea of using masks with large eyes, fixed at the back of the head, for those travelling inside tiger infested jungles, like the Sundarbans. Hunting animals such as a tiger instinctively attacks prey, including humans, from the back. So, when it sees a human and recognizes its front by his face and eyes, he will slink and skirt around behind the person before springing. But if the person has a human mask with large eyes at the back of the head – that throws the tiger off, confuses him, and makes him re-think the angle of attack, and often discourages him enough to let the guy go. Mr. Arun Ram claims to have come up with the idea first and tried out, successfully. But today, his idea is copied by commercial tourist organizations, and he is contemplating ways to either patent or register his idea so as to get some credit and financial compensation. Very interesting person. His knowledge of wildlife, I found, was exceptional. HE was describing various kinds of poisonous snakes and the kind of poison they make etc. Even he came here to meet with the rest of the nine-jewels and take part in discussing folk rice conservation and promotion.

Next- Rabin Banerjee. He is a non-farmer that is committed to spread organic rice farming and has roped in over a hundred farmers of Purulia , many of them women, to reject toxic cultivation and try out organic folk rice variety. He actually changed his regular job, downgrading it to a sort of part time job that paid less, but enough to support his family, so that he could devote more time with the farmers of Purulia. I consider people like Mr. Bannerjee to be rare blessings for India. Thank heavens there are people like these around.

I am tempted to say – someone needs to write about people like Rabin Banerjee – and his unique near single-handed effort to convert more than a hundred farmers of Purulia, many of whom are marginal, female and Rajwangshi (lower caste), into cultivation of organic folk rice. Who needs Bollywood characters when India has so many real life heroes?

But I know, nobody will be writing it and I need to do it myself. So I shall.

Rabin Banerjee and myself at Bhairab Saini’s vegetable patch.

Next – myself – a storyteller. I am doing my job here.

Next to me – Anupam Paul. He is another giant in the field of promoting organic folk rice cultivation in India. He is an agrologist, having done his PhD on the subject. He is employed by the Government of West Bengal, and runs one of the seven Agricultural Training Centre (ATC) in the state. What is unique about him is that six out of seven such ATC promote industrial, chemical dependent agriculture and influence/train local farmers accordingly, following the state policy on Agriculture. But Mr. Paul has the seventh ATC running in the opposite direction. He is involved in conserving over four hundred strains of heirloom folk rice, practices growing them organically without any chemical, and then trains as well as influences a growing number of local farmers, spread across 14 districts (counties) of West Bengal, in support of organic folk rice. He has enough data to prove that indigenous heirloom folk rice, grown completely organically, can match of beat hybrid varieties cultivated with recommended industrial fertilizer. In other words, the benefit of modern agriculture is more a myth than a fact. He is, in my view, another heaven-sent and one of the shiniest of the jewels in this group.

Then comes Shomik Bannerjee. He is a private consultant whose specialization is in Forest ecology and indigenous tribes. He is employed by others to visit various pockets of India, usually involved in people living in marginal conditions, to study and prepare report about them – for clients. He is a very keen observer of various plant species as well as other creatures that make up the biodiversity of our forest ecology. Extremely knowledgable and extremely humble – a very rare combination. From my point of view he has an added distinction – he bought my book – POISON FOODS OF NORTH AMERICA – even before he met me. That makes him not only a rare breed – but perhaps an endangered species. He has also been involved in telling various people around the country – that they they need to consider listening to my story of glyphosate.

Those that need more details of Shouik Bannerjee – he did his graduation in chemistry, and double post graduations in Biotechnology and Forest Management. He has been a free lance researcher for 9 years, with special interest in indigenous seed conservation – in paddy, wheat, barley, oats, millets, maize cotton, Mustard-Rapeseed, flaxseed in Eastern India. As if that is not enough already, he also researches on uncultivated wild foods and forest ecosystems, and to round it off you may add agroecolgy and sustainable farming.

Yes I know. He is one of those.

He and Anupam Paul have been the primary forces behind the scene, to get me to far corners of India and alert people about glyphosate.

Next – Bhairab Saini – the host. He is a farmer from Bankura. We are standing in front of an earth walled farm house of his. Years ago, he was influenced by the rice conservation works of Debal Deb when Debal was working in Bankura. After Debal left for Odisha, Bhairab continued to a) conserve many strains of folk rice, d) encourage more farmers of his family and friends to join up in growing chemical free folk rice, and same time take up some organizational activity in promotion of folk rice in Bengal. He has received help and assistance from the rest, primarily from people like Anupam Paul. He is the one that organized the event in his village for me to speak about glyphosate. He invited me to stay at his farm house. He also helped get the rest of the jewels to congregate.

Black rice being bagged for shipment and sale in Delhi

He has one more distinction, in my mind. Slowly, he is managing to find a market for organic folk rice grown in his village, for sale in urban outlets at various far flung corners of India. He has already sold all the folk “Govindabhog” rice his group cultivated this year, but still has lots of Black Rice as well as Govindabhog derivatives such as rice flakes etc. So he has been busy bagging them. A group including his family and some friends are scheduled to haul nearly two tons of the stuff to Delhi, to join a village fair organized by the Ministry of Women’s affair, headed by Minister Ms Maneka Gandhi, where Bhairab will advertise his wares, hope to sell the rice and firm up more business for the future. If efforts like this catch on, it might influence more conventional farmers of his village to come over to organic cultivation of folk rice. If affluent India recognizes the need for healthy food and start supporting these grassroots efforts, then more and more farmers, of his village and others, are expected to follow the trend. I wish Bhairab’s efforts all success. He is not the only one in this effort, but he is so far the only one I have personally seen, who is engaged in both growing, and trying to bypass the middle man to directly sell organic rice in India to the consumer.

Next to Bhairab are Pradeep Nayak and Shakti Roy, both from Village Panchal, both friends of Bhairab, and both believers of organic rice cultivation. I think both of them will be going to Delhi with Bhairab trying to sell black rice and drum up more business. And we ate lots of organic banana that were ripened on the tree in Pradeep Nayak’s garden. Both of them also did the cooking for us. Mr. Nayak also offered a few rooms of his own home for some of us to stay, since Bhairab’s farm house had only two rooms besides the kitchen, and could not accommodate all of us.

Village girls returning from school

There is one more jewel that was supposed to come but could not due to personal issues – Abhra Chakrabarti.

Edible mushrooms in the forests of Bankura

Edible mushrooms collected from the forest by villagers of Panchal area, Bankura. The spores of these mushroom fungus are collected, stored,, cultivated and harvested by white ants (termites). These are kept inside their anthills in off-season. The on-season starts now, and these spores sprout, grow on stalks with white mushroom heads sticking out. Knowledgeable villagers go looking for them at the right time – around now, cut the stalks and bring them home.

Edible mushrooms collected from the forest by villagers of Panchal area, Bankura. The spores of these mushroom fungus are collected, stored,, cultivated and harvested by white ants (termites). These are kept inside their anthills in off-season. The on-season starts now, and these spores sprout, grow on stalks with white mushroom heads sticking out. Knowledgeable villagers go looking for them at the right time – around now, cut the stalks and bring them home.

These are usually cooked by light pan-frying in oil and then boiled and turned into some kind of curry with spices, and consumed with rice.

One couple that went looking for them at the beginning of the annual mushroom season found these. Other groups I met, returned empty handed. However, the month long season just started. The mushrooms grow only in certain patches of the forests. Some villagers have the keen eye to find them. Others do not.

You may ask – what does this mushroom have to do either with conservation of folk rice, or with the vanishing face of sustainable India. But, I guess you already know the answer.