“There was a movie, in Bengali, with that name – Storm Warning” Neil mused.

“Really ? What did it say about the climate? Was it in English?”

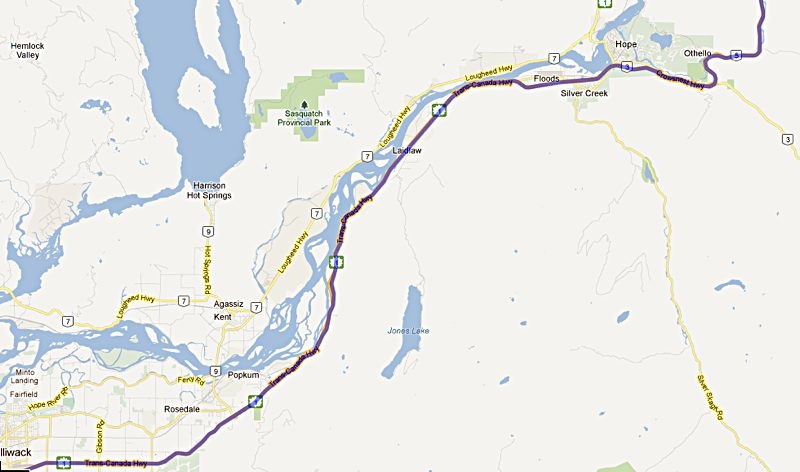

They were sitting on a large boulder by the side of a small river fighting its way through an iced up landscape, early in the afternoon on the Easter Friday, in among the Cascade mountains. They had a few hundred kilometers still to go to reach their destination for the night – in the town of Golden.

They had been discussing climate change, and what might be in store for the planet, for the continent, for Canada and for British Columbia, a very loaded subject. They did not have depth of comprehension – but both knew things were reaching a crisis point, and information was not easy to get because the authorities seem to be either in denial, or unwilling to alarm the public. They were not calling a spade a spade.

Neil picked up a pebble and tossed it down the slope to the edge of the water. He wondered about the high concentration of sharp stone fragments below them. These were not pebbles that were pushed a long distance by a fast flowing river, helping to grind and polish them into smooth spheroids. He briefly wondered if these were crushed from the nearby peaks through past seismic tremors, or broken from the rocks by an ancient glacier and left at the current location. They were not exactly at the foothill of a sliding slope, so they did not get here from a recent rock fall or an avalanche.

He sometimes wished he was a geologist, or at least knew a bit more about geology.

His thoughts returned to Mabel’s question.

He had been talking about tell tale signs of impending trouble, and used the term Storm warning to drive a point. It was then that he remembered the Bengali movie. It wasn’t about Climate change. It was a different time, and the warning was of something else equally menacing for the people of Bengal – an impending famine that would kill millions, in the middle of the second world war. It was now acknowledged that the famine was man made, and not by natural calamity. The world war had something to do with it. The British Empire’s handling of the situation which perhaps indicated less regard for life of Indians than lives of the British, also were likely factors.

Anyhow, the name of the movie – by Satyajit Ray, came to him.

“It was not about climate change, but about an impending famine. It was in Bengali, and the name of the film in Bengali was Asani Sanket, which means storm warning. Somehow, the situation now reminded me of that movie. Villagers at the front line of the worsening situation did not have a good grasp of what was happening and why, since there was no draught and drastic drop of food grain production. Things appeared to go on as it always had. But there were tell tale signs, some folks were beginning to starve for no good reason. News was difficult to come by. Folks did not know things were slowly reaching a crisis point, till the crisis actually hit them in the face.”

Mabel was listening, tilting her head as if cocking an ear in a typical way that only she could do. She was also poking at a bit of snow tucked at the corner of a boulder near her feet.

“I’d like to see that movie, if you will explain the scenes to me. And also explain why and how the famine came by.”

“Hmmm… I have to see if its available on line, or if I can get a DVD” Neil nodded.

“Situation with the coming Climate Uncertainty is not too different. We are living in the information age – with the world wired up and news traveling around at the speed of light. And yet, the silence about the impending storm is mind boggling.”

“And you like Mukherjee and Dyer.” Mabel observed.

Neil chuckled. He had told her about another book, by Madhusree Mukherjee, on Churchill’s actions, or lack of it, with regard to the ill-famed Bengal famine of 1943. And Gwynne Dyer had written a book that he had in the eBook format, and often referred to, called Climate Wars. Dyer’s book was written more like a science fiction, written based on a future date. It did not predict what might happen in the future. Rather, the book pretends that it is already in the future, and is talking about historical things that has happened in the past. But the past involves the future for the current Calendar.

“You gotta read Dyer. He predicts what happens to Canada, but more importantly, what happens to the US-Mexico border and what happens to Mexico, when the world runs short of food and more or less stops selling excess grain in the world market. Mexico descends into anarchy and its population shrinks by thirty or forty million people.”

“My God !”

“Well, you should read it. It is not designed as a science fiction, but a very likely scenario with a lot of supporting comments and explanations. Things do not end up well for a whole lot of countries – and not just Mexico.”

Mabel signed. “What is one to do?”

Neil stretched his legs. “Singularly, there may be nothing one can do. Collectively, surely there are things one can do. But I have a feeling even the strongest of the Climate Change believers and sustainable living proponents are not coming clean and not calling a spade a spade. And that, for me, is a bit frustrating. However, I can understand some of the reasoning. One can compare the public with lemmings on one side, or the flightless cormorants of the Galapagos, on the other.”

It occurred to Mabel that Neil probably had a vivid imagination.

“Lemmings ?”

Neil was watching the reflection of the white patches of cloud on calm waters of the river below them.

“You know what they say. True or not, they explode in population till they are so many that they have eaten through the food source and there is nothing left to eat, and the land cannot sustain such large numbers. A big chunk of them must die in one shot. Story goes that they go shoulder to shoulder and jump in the ocean to drown and die. Some folks say this is not correct, and that lemmings are not stupid. They do not commit mass suicide, but are forced to die in large numbers when their super fast reproduction system goes out of control and the populations shoots well past the sustainability level for a lean year. Anyhow, I have never seen a lemming in the wild, suicidal or otherwise.”

Mabel tossed another pebble towards the water, but it landed short, in the snow. Her folks were not too religious. She had a girlfriend whose mom was a liberal activist and passionate about individual rights and human rights, anti-war, feminism, open borders and so on. But Mabel could not remember her talking about any impending doom with relation to climate or human population, or about the constant degradation of the environment, a move from a sustainable plane to an unsustainable one.

“I do not have relatives or friends that talk or think the way you do, about the declining quality of our environment to the extent that it is an existential threat to all higher order animals.”

———-

At this point, Tonu stopped and looked up at the cream painted ceiling of his study. It was quarter to six in the morning of Saturday, a week after his trip to the mountains. It was going to be a sunny day, and he was planning to check out the Squamish estuary area in the morning. It would be a hundred kilometer northward drive along the sea-to-sky highway. The ocean, a tiny finger of the pacific, pokes into the land with towering mountains on both sides. The Squamish river meets the ocean at that point, creating a narrow strip of sea level estuary, rich with its own eco-system and wild life.

Meanwhile, he had woken up at his usual early hour and contemplated writing a few more pages. There was no important emails waiting for him, and the earth had spun a few more degrees without further incidence other than the general degradation of things.

He wondered if Neil, his creation, should be influenced by the paintings of his, Tonu’s, father. Tonu remembered the sketches and paintings his father worked on, mostly following the general theme of simple rural life and landscape that were captured on board. He was a student of Nandalal Bose, the esteemed Indian artist of the first half of last century, who himself was a student of Abanindranath Tagore and was influenced by Rabindranath Tagore during his days in Santiniketan. Depiction of rural landscape and rural lifestyle had priority in their view. He, Tonu, thought of this movement as a theme that had two objectives. One was a recognition that rural background was where India was culturally, aesthetically, artistically, economically and spiritually anchored and rooted. Therefore this back to the village artistic movement was not a backward motion against modernism, but a realization that modernism in India had missed the sustainability bus.

The second part of the movement was to create an appreciation in the collective psyche of the Bengali and Indian middle class, of the timelessness and beauty of things simple and rural. India was fast creating an additional layer of a caste system, between the city dwellers and the villagers. This psychological as well as economic and cultural division, over and above all the other divisions that man had created for himself in the Indian subcontinent, was a further humanitarian blow to the evolving social order in India. Rabindranath Tagore, the poet with a vision, realized that this needed to be eradicated. That vision showed up everywhere, including in the art created in his time and in the immediate aftermath of his demise.

Modernism, however, was going to come to India, and it would ultimately muddy the water about rural and urban divide as well as take the focus away from the village so much, that future artists would be, Tonu felt, hanging in suspended animation, attempting to give their art a somewhat “ethnic” Indian flavor, while same time pandering to the western world for recognition, and take advantage of the recent western accommodation for appreciation of non-western art forms.

The whole thing, Tonu felt, was bizarre. Art was supposed to imitate life. But life itself had gotten so artificial, that this falseness was bound to be reflected in art, especially of the second and third generation of artists that come out of the same school as founded by Tagore and now spread across the globe. And those that still remained anchored to the original theme of rural India, faded in the backwaters in the world of Indian art. Artists that cannot draw a tail on a donkey, but can make false copies of western cubism or impressionism, where the hot topics in the drawing rooms of the new rich. Industrialists that have come into money, and feel the urge to promote art – define art in their own myopic view of India and the world, and the rest, Tonu felt sadly, is history.

However, this sad story too needed to be told, in his own tiny way, as the world, including India, were busy recklessly following a false modernism and sliding down the ever steepening slope of an existential crisis with regard to squeezing the planetary lemon dry.

He was hesitant about jotting down his feelings openly, as he personally knew a lot of people that came out of the art school. Besides, he was no expert in art. In fact, he was no expert on anything. And yet, he was tired of pseudo artists and pseudo writers and false intellectuals, unscrupulous industrialists and phony political ideologues who unnecessarily muddy up any issue till there is no clear perspective left on any topic. He was also tired, in a way, at the hapless public dancing at the end of the trivia string.

But his comments were not directed towards people he knew. It was at the general direction where mankind of taking itself and the rest of existence as humans could perceive it. To him, these are connected. He could relate to the changing scene in Canada, to that in India, or USA or Africa. And most of it was man made. Most of it was unsustainable. Most of it was a direct result of man’s increasing level of interference with the planet’s health.

One of the earliest visionaries to have realized the imbalance, at least partially, was perhaps Rabindranath himself. He saw it as a grotesque takeover of india’s cultural, spiritual and aesthetic steering wheel by a newly emerging urban class that lacked a depth of perception, or willingness to investigate long term effects of their presumed lifestyle goals, and a blind intoxication with a western definition of development that was itself bankrupt as a perpetual formula.

Tagore instinctively understood that the urban class may turn out to be the agent of destruction for India, unless it could be made to appreciate the need for a healthy balance between the rural and the urban. The western societies understood it. But a modernizing India did not. Tagore spoke about it and wrote about it. But it is doubtful if his countless admirers and hangers on actually understood the cause of the poet’s anxiety.

Tonu’s father used pastel and earth colors on boards more than water or oil color on canvas. Tonu had spend hours with his father, grinding hollow rocks on a grinding stone, extracting earth colors, which would be solved in water and kept in glass jars, to be used on future paintings on boards as well as in murals on walls. Collecting earth colors from the earth was a big adventure for him in his youth, and likely played a big role in his love for undisturbed nature and how it trumped man-made alterations of the landscape.

The thought of his father’s sketches and paintings were not a random intrusion into the flow of the story where Neil and Mabel were traveling into the Cascade mountains of British Columbia. There was a connection here.

His father drew and sketched scenes that, in Tonu’s own life, had slowly vanished from those very spots where his dad had observed them. Those open lands had now been concretized, asphalted, civilized, crammed with people, turned into a filthy near slum urban sprawl.

This, to him, indicated two things that were inter-related and going on, generation to generation, perhaps all over the world. One of them was the destructiveness of an over-producing, over-consuming, over-altering, over-mechanizing civilization. The other was an ever greater expansion of the human population.

So, on one side, each human in progressive generations was demanding a greater and greater footprint for himself on this planet. Then, on top of it, people have brought more people and even more people, on the planet, each striving his best to increase his own size of footprint. This was another kind of an out of control snowball – a positive feedback loop gone wild. This was, in Tonu’s mind, not too different from what is happening in Europe, in the Americas, or even in the Antarctica. The difference should not be measured between regions. Rather, the change is within. Greenland might appear remote and cold compared to Singapore. But Greenland is less remote, less cold and less pristine, than Greenland was a century ago.

And so, Tonu decided to include his own fathers painting into the story, but pretending that to be Neil’s recollection of his own father. Tonu had, in that way, converted his own dad from a real to a fictional personality. One that was, just like the scenes he painted of, slowing fading from the planet.

————

Neil nodded. “Its not that I have a lot of relatives that scream about the changing world in any realistic way. My grandmother used to talk about times when things were very cheap and how everything costs so much more these days. My cousins might talk about how it was easier and more relaxing to be in school and college in our times and how things have gotten so stressful in India for a student. The pressure to perform is so great, the stakes are so high, that sometimes a student is pushed into committing suicide because she or she scored 95 out of a hundred instead of 99.”

He thought for a while, constructing the views and images swirling around in his head.

Mabel took a sip of coffee from the cover of the flask, which also served as a cup. Neil took the cup and took a sip himself. They had gotten to the point of sharing their coffee. He liked it with milk and sugar. She liked it without. They had met halfway – with a dash of milk that barely turned the color lighter, and a spoon of sugar for the entire flask of coffee. Life was a compromise. Neil was getting used to it. So was Mabel.

“But no one”, Neil continued, “actually spoke about the inexorable push of human civilization that engulfs the planet as we know it. But, generation by generation, the change is happening, I feel somewhat certain. Take life ten generation ago. I cannot name folks ten generations back in my line, but I can guess how things were, a couple of centuries ago, just as the British, for example, and the French and the Dutch, were increasing their trading with eastern India, and how the repressive society of religious orthodoxy, social taboo and enlightenment were slowly permeating through the village life. I can imagine how a high caste Hindu or a Muslim would have multiple wives and how poverty drove people to do things he would not otherwise do. How a woman had to adjust to the lifestyle dominated by men at all levels. How surviving from day to day involved not only eating enough and not getting sick with cholera or typhoid, but also not getting bitten by a cobra or taken by a crocodile in the water or attacked by a tiger in the field.”

He paused for a moment, looking at Mabel. She watched him, wide eyed. “And then, I can guess how, even in their times, things would change, generation upon generation. How jungles will be cleared, wood would be sold, tigers would retreat further away. Extra housing and population would bring safety on one side and more sickness and infection on another. Life would be changing, generation by generation, even in their times. And if one was to look at it from afar, it would have been possible for them to use those changes they saw in a small scale, to project on the planet and on mankind, on a larger scale for future. Those that did contemplate these issues, and made predictions, right or wrong, where considered either mystics, or God men, or pundits, or mad men. But, change was happening then, and it is happening now. MY own dad made paintings and sketches of rural Bengal not five miles from his home. Today, that scene is no more there. It has retreated, just like the tigers of a few centuries back. Things are constantly retreating into the background, and getting smaller in the distance, till they become a point on the horizon. Finally a day comes when it is no more there. It has retreated into extinction. And this change is not for the better.”

Mabel had seen a handful of Neil’s dad’s paintings that Neil had mounted on his wall.

She thought of telling him how she loved those paintings. But somehow, that seemed not an appropriate thing to say. The scenes he drew were gone now, according to Neil.

“Some day, you have to take me to Bengal and show me where you grew up, and where your dad made those paintings.”