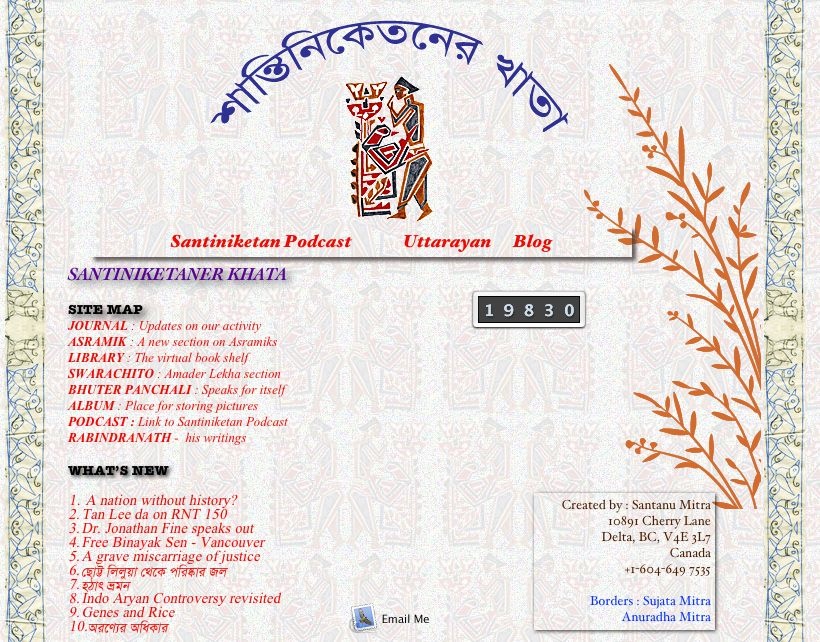

It was time to close my Khata blog down. Like so many things, the Khata web site was one that was so exciting to start and open, and now, feels like a discarded old house.

I remember going through the Binoy Bhavan road, on the outskirts of Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, where the rows of brick houses stood in line before a narrow asphalt road that bent around a cemented well. We spent some of the growing up years there. Last time I saw it, it appeared dilapidated, as if no one lived there.

Santiniketaner Khata was opened with some personal fanfare. The excitement was mine alone. Those days, the world of Santiniketanites was just getting smaller through internet. A new avenue was opening up for re-establishing contact with each other. Folks were rediscovering old friends. New friendships were blossoming. Times were great.

It would not be long however, before the frog-in-the-well mentality of the general masses, of which the Santiniketanites were no exception, would surface, irrespective of if the frog in question lived inside the well, or outside.

An aversion to doing anything together, constructively with a long term goal, was the signature trait of this group. The group would be recognized not for all it would do, but rather, for all it did not do. As a result, the atmosphere would follow slow atrophy and decay, leaving behind some folks engaged in reminiscence and trivia.

I had hoped that internet might provide a new and unique bridge allowing entry of fresh thoughts and a new sense of belonging and camaraderie. The new atmosphere might help glue together a disparate group of disconnected and remote number of ex-students with folks connected with Santiniketan. The new media might somehow usher in a meaningful transformation, inject new life into an otherwise moribund near non-existent entity, that of the ex-students and Ashramites of Santiniketan.

What eventually happened is, to me, rather less than meaningful. The world of Santiniketan turned out to be a two headed monster. One one side, there is this supreme apathy. This apathy is not just extended towards the legacy of Tagore, but covered every issue that was not of some direct benefit to the person. On the other side, the sheer lack of sincerity, extent of laziness and selfishness, compounded with dishonesty left me dumbfounded.

I was naive. I had not realized that they were in essence same as the rest of humanity, which too lacked humanity to deal with the issues of today. My fault was expecting these Rabindrik uber-culturists to be above average. They turned out to be actually much below average. What a let down!

And so, the Blog of Santiniketaner Khata, which in english might mean the notebook on Santiniketan, contained mostly my own writings, and almost no one else’s. I tried within my means to encourage others to contribute and engage in healthy debates and discussions. It would cost them nothing to post there. But I did not get much luck. Exercising one’s brain in constructive energy appeared to be counter to their concept of appreciating Tagore.

The very name, Santiniketaner Khata, began to lose its appeal. The web based blog-notebook contained its share of ideas and observations. But ultimately it turned out as useless as most anything that Tagoreans have done so far. It turned useless because few read its content, and even less would contribute any idea or add any value to the topics. The pages of that blog would wither away, and drift in the wind along the dusty grounds of Santiniketan. I could well imagine it.

And so, it was time to close it down. I wondered if Santiniketan too should just close itself down, and blend with the red earth of Birbhum. Perhaps one day it could rise from the ashes again, resurrected in a second coming.

I could imagine how Tagore ended up writing:

Where knowledge is free

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments

By narrow domestic walls

Where words come out from the depth of truth

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way

Into the dreary desert sand of dead habit

Tagore was describing, I felt certain at this point, what he had observed about the middle class around him, and how they were responsible for perpetuating the crippled society in India. He could see that removal of the British was not going to make things much difference to the rudderless Indian society.

চিত্ত যেথা ভয়শূন্য , উচ্চ যেথা শির ,

জ্ঞান যেথা মুক্ত , যেথা গৃহের প্রাচীর

আপন প্রাঙ্গণতলে দিবসশর্বরী

বসুধারে রাখে নাই খন্ড ক্ষুদ্র করি ,

যেথা বাক্য হৃদয়ের উৎসমুখ হতে

উচ্ছ্বসিয়া উঠে , যেথা নির্বারিত স্রোতে

দেশে দেশে দিশে দিশে কর্মধারা ধায়

অজস্র সহস্রবিধ চরিতার্থতায় —

যেথা তুচ্ছ আচারের মরুবালুরাশি

বিচারের স্রোতঃপথ ফেলে নাই গ্রাসি ,

পৌরুষেরে করে নি শতধা

The English translation was never as good as the original in my view, and so I copied the section from the original here. The translation was Tagore’s own, and he had changed the words around, perhaps out of concern for the western readership, who might not interpret the literal translation of the Bengali in the right spirit. I however find his original Bengali text a lot more forceful and direct.

I considered the sentence যেথা নির্বারিত স্রোতে দেশে দেশে দিশে দিশে কর্মধারা ধায় অজস্র সহস্রবিধ চরিতার্থতায়. Tagore changed the translation of this sentence. He talked here about that environment where folks will take great ideas to far flung lands and convert them into countless thousands of deeds in an endless stream of constructive endeavors. Tagore decided to change the expression when he said, “Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection“ but I liked the Bengali text better. Either way, Bengali or English, his wish was not to be fulfilled by people that had the maximum exposure to his views – by a very long shot.

We, the Tagorians, did not carry any of the great ideas to any far flung land and did not convert anything into timeless deeds of human endeavor. There were no tireless striving or stretching of arms towards perfection. Only time the arms stretched were to line one’s own pocket, or to beat one’s own drum. We merely buttered our bread while providing a suitable lip service to Tagore’s grasp of beauty, language, rhythm, and rhyme – restricting him to the rank of a mere poet.

He also used the words পৌরুষেরে করেনি শতধা. He was still talking about that environment where the manhood of the Bengali bhadralok clan, and by extension to the Indian middle class had not been neutered by thousand year old layers of dead social customs, religious bigotry, ethnic shortsightedness and hollow status and caste segregations.

Fast forward a century, and some things are the same, while others have gone far worse. The babu still shows signs of being morally castrated.

So, I got disenchanted with the Tagorian diaspora, and stopped pushing the Santiniketaner Khata. Nobody cared. By closing down the Santiniketaner Khata, by diverting the direction of the Santiniketan Podcast, by deciding to close down the Uttarayan bulletin board, I was seeking freedom from the well, wishing to leave the fellow frogs to their devices. I was tired of the collective croaks.

Is that all?

Well, there is still this one thing. I was still alive, and having discarded the Achalayatan or the immovable unchangeable dead boulder of Santiniketanism, where I was spiritually cloistered for most of my life, I still have energy and exuberance and a wish to engage constructively on something, with someone, somehow, somewhere, on some cause. I was not quite the Rabindrik rebel-without-a-cause. I had a cause, but it did not sit well with the place-without-a-cause. Santiniketan represented a state of causelessness. And so did Santiniketaner Khata – a reflection of the real thing. Santiniketan was full of such rippling reflections from a myriad of angles – all of them gaunt and displaying signs of decay.

Meanwhile my wish to remain a sizable and recognizable contributor to the history of my own ramblings is still very much present. In other words, I was not yet dead.

Khata can be closed, but Tonu was not yet burnt to ashes or buried under six feet of earth, or submerged at the bottom of the ocean. I was alive and kicking, and I wished to leave behind my views, my hopes, my aspirations and my frustrations, and how I felt about the whole situation with the Tagorians.

He had written himself – আমি ঢালিব করুণাধারা, আমি ভাঙিব পাষাণকারা, আমি জগৎ প্লাবিয়া বেড়াব গাহিয়া আকুল পাগল-পারা. He wrote in in his youth, and edited it later, and trimmed it a lot. But, as an early teenage lanky and tall boy, he had been to the Himalayan foothills and seen how the glaciers, locked up for years among the rocky peaks in high mountains, were slowly released by the warm rays of the sun. At that time he did not know that the warming of the sun was going to be assisted and accelerated by man, and that the glaciers would vanish one day. To him, at that time, the release of the rock bound ice into the liquid flow of life supporting river was a sign of freedom, or release from imprisonment, a blossoming of life itself.

Those lines in Bengali meant, in my translation – I shall pour forth a river of compassion, I shall break out of the stone prison, I shall inundate the world in a deluge of exuberance, romping and singing as if one possessed.

Well, I was not the headwaters of the Ganges, but I too had some pent up energy still left in me. And so, even with the Blog site on Santiniketan closed, I would not only continue to write, I would even write about this very shutting down of my blog notebook. For anyone with an over-fertile imagination, my opening and then closing of the site, could well be taken for a cyclical story of a beginning leading to an ending which in turn triggers a new beginning. It follows a similar cycle to the story in that famous Tagore Poem, of moisture that rises off the ocean and gets trapped as snow on the Himalayas, only to be released by the warmth of the sun and come cascading down as life sustaining river, returning back to the ocean, only to be reborn into another cycle of being vapor, ice and water. One could think of this as creation and destruction locked in a conjugal dance of the cosmos in the ever-dynamic world of Nataraja, the God of dances.

Anyhow, I became a disenchanted devotee returning disillusioned from a disappointing pilgrimage. I was a pilgrim that had gone to the holy land only to find that it was not quite so holy after all.

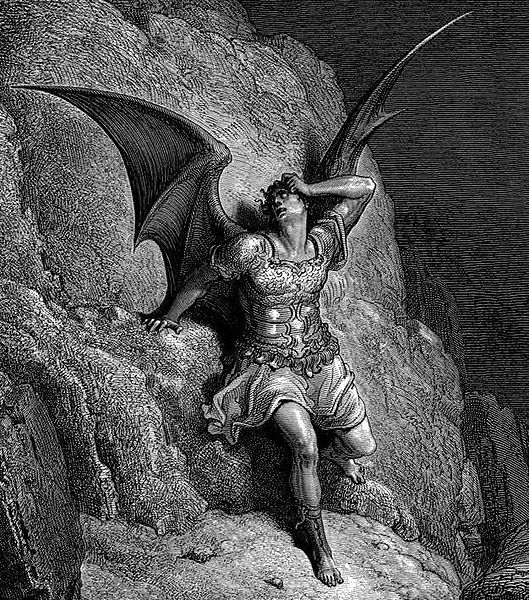

Milton had written that epic, over four centuries ago, about the Biblical tale of the fall of man to the lure of Satan, and expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

Satan, the antagonist of John Milton's Paradise Lost c. 1866

Well, I had neither seen nor been lured by Satan, the flying bad man. But then I was not Adam either. For me, the loss of paradise was not because man was banished from it. It was rather a case of there being no paradise to begin with. Man will make what he will of the place he lives in. And, once Tagore was gone, my holy land had degenerted eventually to a cultural wasteland. Worse, it was on its way to being a sewer.

I could not quite accept it as nobody’s fault. It was the fault of all, starting with the army of Rabindra-disciples that make a career out of squeezing the Tagorian lemon. They brought forth the greatest expansion of a new species of lemon squeezers.

My paradise had no place for lemon squeezers.

I had lost my paradise when I was confronted with its non-existence.

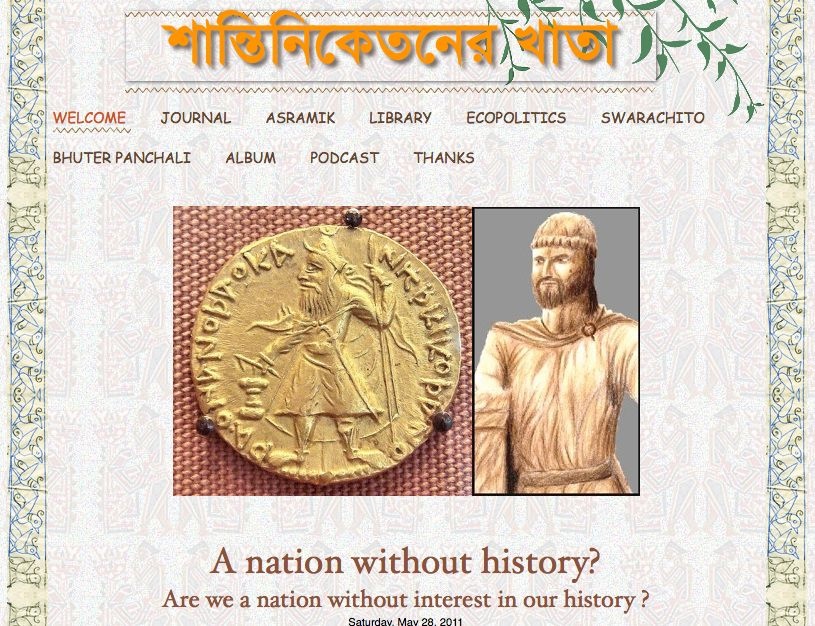

And thus, I went over to the opening page of the Khata, and copied the top section into an image, as a snap shot before the dead body could be placed in the morgue. My pilgrimages was over.

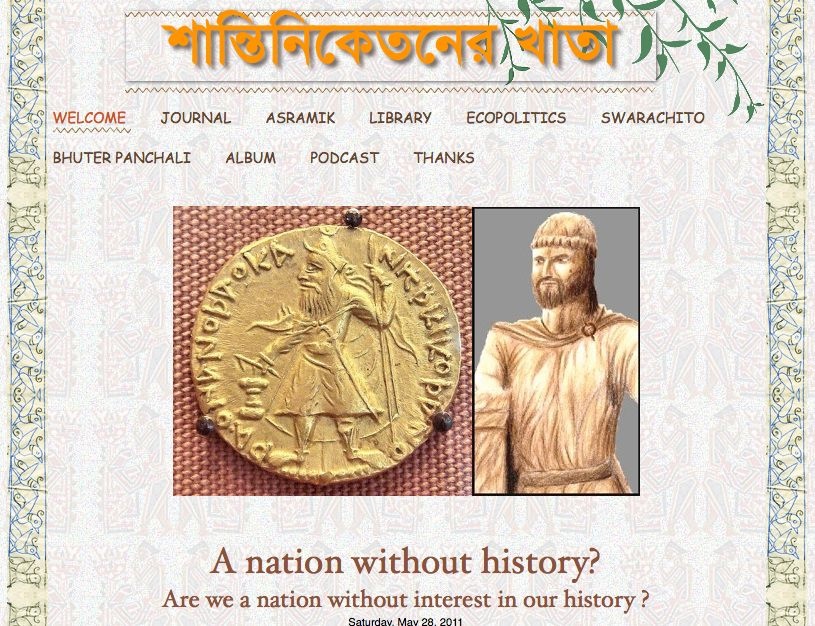

I looked at the partial image of the home page of the Khata blog. The image included a stooping man with wild beard and wearing a sort of an asian frock coat, armed with a spear on a gold coin with letterings I could not follow and did not remember which language it belonged to. Next to it was an artists rendition of the same man, perhaps a bit younger. He was Kanishka. The front page, like the cover of most magazines, was supposed to change with time. The last entry was about Kanishka and my question – if folks in India were at all curious about their own past. Whether Indians cared about their history or not, that was my last entry on that site, which itself had become part of history.

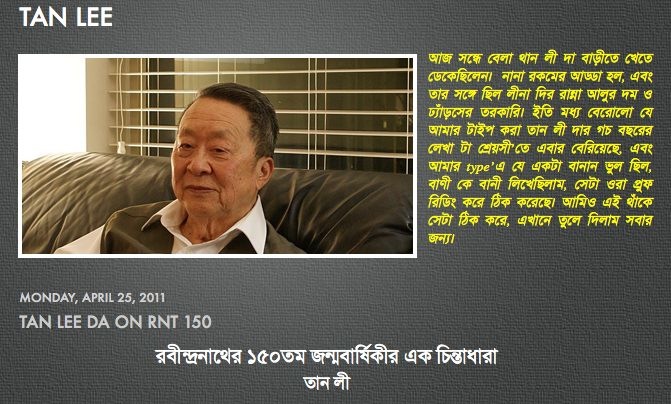

Moving on from the front page and the most recent article, I came upon a picture of Tan Lee da and his presentation in Bengali on the occasion of the 150th birth anniversary of Rabidnranath Tagore. I too had joined whole heartedly to participate and contribute to the global celebration of the event. But that was then. I have since lost considerable amount of steam for this endeavor, and have begun a serious introspection on the purpose and significance of these efforts. Today, I do not feel convinced that such celebrations are worth much, and what purpose it at all serves.

But thats a different issue. Right now, I felt sad that Tan Lee da is no more as agile and alert as he used to be. Just last year he produced that beautiful writing and poem about his beloved গুরুদেব (gurudev Rabindranath Tagore). And I had put that up on the ASRAMIK section of the Khata blog.

Myself and Tan Lee da have some work to do. I also intend to coax him into taking the first step towards writing his book.

But we remain respectfully disagreed on the issue of helping to promote the vision of Tagore. The differences are subtle, and Tan Lee da and Leena di do not disagree with my view wholly. Nonetheless, we stand apart on this issue at this stage. To me, it seems both pointless and misdirected, to expend energy to promote Tagore to the outside world. To me, he should have been better understood by his own country men, starting with people of Eastern India.

Anyhow, the best way to promote his views, at least in my eyes, would have been to promote the kind of a world that he tried his best to create, inside India, and internationally.

I have come to realize that Tagore was an excellent writer and essayist in more than one language. There is really no need to translate his world view or socio-cultural views about India or the east for western consumption. Some of the best analysis on these have been done by people that do not know Bengali and have read as much material written by Tagore himself as written by others about Tagore.

India is not ready for Tagore. The great herds of Tagoreans are cultists without a grasp of the man. The East is not ready for him either. And neither is the west ready for his brand of Internationalism blurring the boundaries of national fervor. I do not see the point of running about everywhere, trying to force an uninterested world to think about universal humanism. We were not changing the world. We were not even promoting Tagore. We were promoting ourselves – selfishly at Tagore’s expense.

It was time to put Santiniketaner Khata into a mothball. I could have written about Tagore, the east and the west and his efforts at contemplation on what path laid ahead for mankind, but, why not write here in my new blog? At least it does not have the name of Santiniketan as a false promise. It is in my name.

The East is in a deplorable state of affairs, in a headlong and absurd rush to ape the West. Meanwhile, the West is busy hurtling towards a financial and civilizational wilderness. The world today is very very different from his times. The world actually has turned on its head, and yet folks are drugged into complacence and do not find it odd that the landscape appears upside down.

Tan Lee da’s case is different. He is mentally too attached to Tagore and Santiniketan. It is a faith for him, and not a matter of logic. Santiniketan represents a pilgrimage, and he will go there as long as his health holds up. To him Tagore is the ultimate balm for his soul and the image of Tagore in Santiniketan is indelibly etched in his mind. This image is his morning star, his sunset over the horizon. It would be cruel, as Leena di said, if one was to advise him against going there because of health reasons.

Tan Lee da remained a lifelong pilgrim. His spiritual horizon was illuminated with the glow of Tagore. He never lost his paradise. It stayed with him, wherever he went.

He had not lost it, but I had. I did not wish to keep returning to Santiniketan. It offered memories, but I wished to make new memories, watching the mountains the streams and the glaciers myself. I wanted to see the eternal dance of creation and destruction with my own eyes, and compare them with Tagores expressions. I wished to observe humanity with my own eyes, and apply myself to it. I was mindful of Tagore’s efforts in promoting an universal humanism, but I needed to experience it myself, and outside of Santiniketan. Santiniketan did not offer either universalism or humanism, or much anything else worthwhile, anymore.

I had lost my paradise, but was at peace with it. I was happy to let go of the symbol, while holding on to the real thing. Unlike Tan Lee da, or my parents, or uncles, or so many others, I had not seen Tagore with my own eyes. And yet, I had understood him enough to know that I did not need Santiniketan.

It was time to let go of a dead habit.

It was time to close my roadmap to and for Santiniketan.